IV. Presenting the Data: Categories and Schemas

IV. Presenting the Data: Categories and Schemas

A World Made by Travel makes public not merely a digitization but a datafication of A Dictionary of British and Irish Travelers to Italy, 1701–1800, compiled from the Brinsley Ford Archive by John Ingamells.1 The tool at its core, the Grand Tour Explorer, combines the digitized text of the Dictionary’s entries (4,985) and the more than one thousand newly created ones (1,022) with an interface that enables deeper exploration of the data drawn from those same entries. By transforming the rich and varied information of the original print entries into a multidimensional database, the Explorer re-animates the thousands of travelers that appear in the print Dictionary’s pages. Among other things, this process has centered hundreds of women who were previously subsumed under the headings of other travelers (by and large, men); foregrounded overlooked and otherwise “hidden” figures, such as servants; and made visible and quantifiable the unevenness of information preserved across this world of travelers.

A Database of Travelers

While the scholarly essays in the previous section constitute an exemplary subset, there are as many ways of working with the Explorer as there are research questions. This section, “Presenting the Data,” systematically presents and explains every facet of the categorizing process that led to the creation of the Explorer’s data, making explicit the choices involved. To turn historical information into data is to formalize and interpret it. Data is always constructed to varying degrees, such that it is crucial to cultivate an awareness of both its provenance and its construction. Joanna Drucker, Miriam Posner, and Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein have all emphasized the importance of data construction and editing, and Claire Lemercier and Claire Zalc have recently written that “building data from sources and creating categories that do not erase all complications is not just the longest and most complicated stage of research; it is also the most interesting.”2 It is vital to understand not merely what the data in the Explorer represents and means but how its representation and meaning relate to its construction and its sources.

The principle of connecting data documentation to data presentation is important in two senses. First, to be transparent about this process is to acknowledge the labor that went into it and to guarantee the documentation essential to preserve it. The semistructured nature of the Dictionary’s biographical and travel information facilitated a systematic approach. The consistent use of abbreviations for certain life events and for certain movements of the travelers enabled a computational parsing of these as regular expressions. But this parsing was always guided by specific and carefully thought-out decisions about which categories to use and how to name them, how to resolve ambiguities, what to include, and what and how to count. Each of these decisions, in turn, directed the parsing work in its several iterations, the results of which ultimately constituted the data and its structure. The process itself imbued the data with meaning and determined how it would be preserved and shared. It entailed making decisions about a range of questions, including the organization of the temporal and spatial dimensions of historical information laced with uncertainty, the structuring and use of gender or occupational categories, and the translation of a large, complex, and dynamic database into static and easily downloadable tables.

Second, to understand the construction of the data—its multiple categories and how they relate to one another—is to unlock new ways to do research, make arguments, and create knowledge. Christopher Warren, when writing about the data in his computational study of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, coined the phrase “historiography’s two voices” to distinguish between data serving as an index of the past as such and data serving as testimony to the ODNB’s own contingent making.3 The Dictionary of British and Irish Travelers to Italy, with its approximately six thousand lives, is by no means comparable in scale to the ODNB, with its circa sixty thousand. It is possible for a scholar to carefully read the Dictionary in its entirety, whereas it would take 137 years, as Warren reports, to read the entire ODNB at the rate of one life per day.4 But the two books share a risk when it comes to datafication—namely, that a data-driven approach would merely illuminate the reference work itself. To push beyond this requires careful and self-conscious handling of the data and open-minded exploration of the intersections between its various dimensions.

* * *

The Dictionary also differs from the ODNB—which is dedicated to “significant, influential or notorious figures”—in its inclusion of people about whom not much is known.5 This is a remarkable achievement and offers researchers a rare opportunity, which digital technology facilitates but that relies conceptually and materially on a long tradition of work. Already in 1979, in their famous article “Il nome e il come,” Carlo Ginzburg and Carlo Poni intervened on the divide between microhistory and quantitative history with a proposal to combine prosopography with nonelite history. They advocate for tracing a name across archives as a way to bridge the gap between lived experiences and larger dynamics.6 This bridging of multiple archives is precisely what the Dictionary’s many authors have done, from Brinsley Ford to Ingamells to their collaborators. The Dictionary’s entries meticulously reconstruct piecemeal attestations found in assorted archives and other primary and secondary sources, offering consideration to the possible, fragmentary, and often otherwise-unknown lives of the tourists. In doing so, the entries reconstruct an expansive picture of the Grand Tour that includes lesser-known travelers alongside the famous ones, providing a breadth that is more fully realized with the creation of over a thousand additional entries in the Explorer.

The fact that there are 177 names in the Dictionary followed by the words possibly or probably lays bare this painstaking work of identification and underscores the many instances that lack secure confirmation. The Explorer’s subsequent datafication of the Dictionary takes this multidimensional tracking and identification of names (and even of those who are unnamed) even further. A World Made by Travel aligns with other digital projects dedicated to the recovery and preservation of more lives than could easily be handled as data in the analog past, offering the ability to move across hundreds or even thousands of biographical records, from individuals to subgroups to the whole.7 Expanded and digital prosopographies can yield significant insights precisely because they can be interrogated along multiple dimensions and at various scales. They don’t just operate at a close or distant level but along other axes: the aggregate, the visible, the uncertain, and the unknown. But remembering that these traces of past lives were not born digital should be part and parcel of any effort to preserve and understand them. No historical data set represents an exhaustive record of the past—nor does any archive—and working with the Explorer data requires understanding limits, as well as how to press on them for meaning, so as to return us to the archives with fresh eyes.

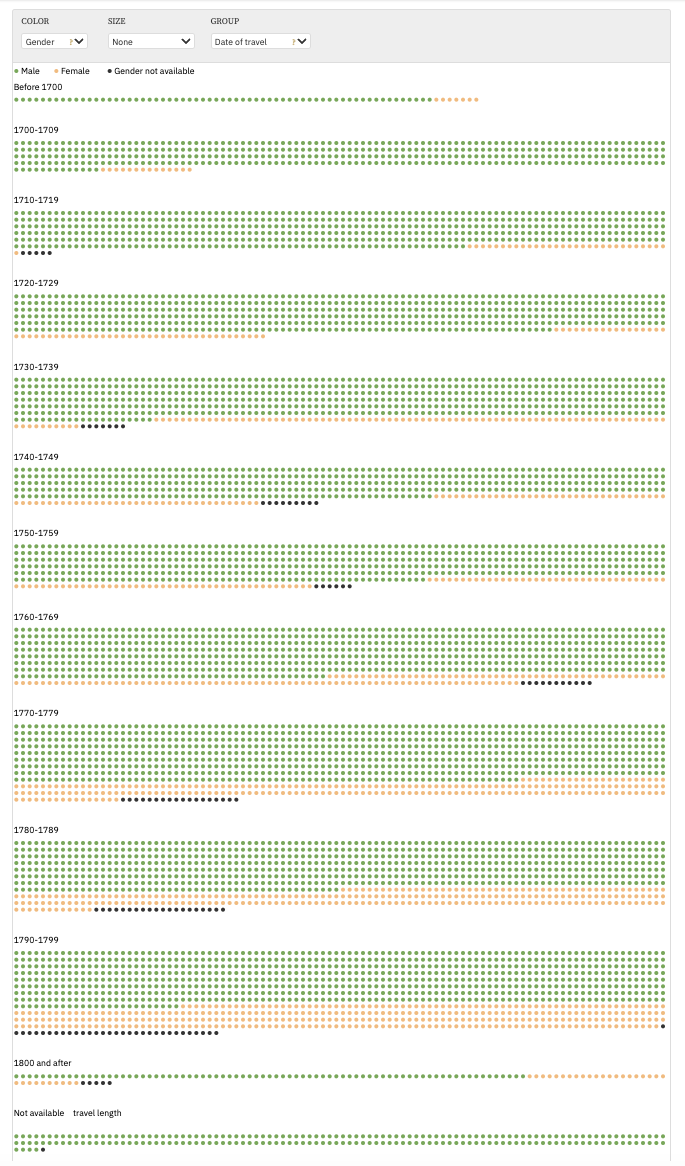

A brief look at the data for the most numerous travelers among the “hidden figures”—the women—illustrates this point. Searching the Explorer by gender across the entire century covered by the Dictionary displays 955 women, less than 16 percent of the total number of travelers. But considering the year in which travelers set off on their tours creates a temporal distribution of women travelers across the century and shows that the number of women travelers increased both in absolute numbers and in proportion to male travelers over the course of the century (see fig. 1 and also Rosemary Sweet’s analysis). From just over one-tenth of the travelers in the 1710s, they come to represent between a quarter and a third of all travelers after 1790.

Adding another data point, that of age at the time of travel, brings further nuance. It is possible to calculate ages for 2,439 travelers for whom we have dates of birth. Overall, the youngest traveler’s age is zero and the maximum is eighty-five, but the average age is just under twenty (19.81). One can differentiate by gender as well: of the travelers with dates of birth, 267 are women (152 of whom are what I am calling “hidden figures,” newly identified for the Explorer).8 The oldest (known) age for a female traveler is sixty-six, much younger than the oldest man. Does this difference mark a disparity in sampling or a meaningful pattern? Only drilling further into the data and looking at the stories of the oldest travelers will begin to offer an answer. Once the travelers whose ages are zero—that is, those born in Italy—are removed, the average age of travel goes much higher, both for women and for men: 28.5 and 28.1 years, respectively. The fact that the number of women and men recorded in the Explorer’s database as born in Italy is almost identical (forty-two and forty-six) confirms the representativeness of our data. But given the disparity in overall numbers for women and men—disparity both in absolute numbers and in the amount and type of information formalized across various dimensions within the database—one should look further into the data and, indeed, beyond the Dictionary to fully appreciate the meaning of the average age of travel for men and women.

This brief dive into some the Explorer’s data counting and intersecting of categories also underscores how much understanding women’s presence in the Explorer data depends on peeling away layers, deciding what to include and how, and asking follow-up questions; for example, in this case, which letters, journals, and archives attest to women and births in Italy? This means working on both a granular and an aggregate level, looking for features pertaining to specific individuals while ascertaining broader trends. To come closer to the lived experience of the Grand Tour and furnish a fuller account of its female travelers requires the inclusion of more and more widely representative individuals, as well as the careful examination of multiple intersecting data dimensions.

As Anna Geurts recently wrote, there has been a surge of studies in the past two decades that center on female travelers, with Dolan’s 2001 Ladies of the Grand Tour serving as a leading example.9 Geurts’s intervention is critical, calling into question these recent works’ positing of a typically female traveler’s gaze. Working with seven accounts from the 1790s, Geurts calls for a more sustained investigation of the diversity of women travelers’ motivations and experiences in relation to age, social status, and personal responsibility. This appreciation for the “irregular shapes and forms” of women’s tours can be expanded to many more women with multidimensional querying of the Explorer data. By combining gender, date of birth, and travel year data, Rosemary Sweet has already shown that by the end of the century, women are more represented in the Explorer database than the young men who were traditionally understood to be the typical Grand Tourists. Catherine Sama, while focusing on the Italian painter Rosalba Carriera’s networking with British travelers, detected a particular bond in her relationship with Katherine Read (1723–78, travel years 1751–53) and Elizabeth Broughton (d. 1734, travel years 1691–1734). The question of who counts as a traveler can be expanded by looking at the hundreds of women in the Explorer and distinguishing between those traveling with husbands or on their own, or with children and with parents. How to categorize someone like Anna Maria Collins (d. 1763, travel years 1713–27), who was born in Italy to long-term residents but embarked on a reverse journey by marrying the traveler Willoughby Bertie (1692–1760, travel years 1722–25/27) and moving with him to a post–Grand Tour life in England? As John Brewer urged us to ask, “Whose Grand Tour” was it? The sheer variety of female experiences in A World Made by Travel awaits further study.

Going beyond the dichotomy of distant versus close reading, historical data research can operate at a range of scales in between dimensions, while holding space for outliers, too. Among the women travelers with the latest travel dates in the Explorer, making journeys at the close of the century, are Caroline Creighton (1779–1856, travel years 1785–90) and Elizabeth Acton (1806–47, travel years 1806–29), one born in Italy and the other born outside of Italy. Both women were also the subjects of portraits (see figs. 2 and 3), and it is moving to come face-to-face with them—especially given the disproportionate focus on men in typical Grand Tour portraiture—after surveying so many numbers, graphs, and dots.

Of course, the promise of digital prosopography is that it can also illuminate those individuals without portraits or even those barely remembered. Understanding the data categories and their interconnections (including how they refer back to archival research) is essential for exploring the new prosopography of the Grand Tour that the Explorer enables.

The complexity of each data categorization—and how the categories within each overlap, diverge, and interact with others—is best understood when presenting them individually, as is done below. But all work together structurally as depicted in the data schema in figure 4, which is a graphic representation of the organization of the data and of the relationships between dimensions. At the center is the main structuring principle of the data: the entry, marked by a unique identifier (the Entry ID number). Different colors distinguish different types of data connected to the entry: biographical data, travel data, and indexical data.

The data schema in figure 4 represents the full scope of the possible data categories that the database structure is designed to accommodate. But there is no single entry for which all the categories are populated, and how populated any one category is across the database varies greatly, as well. This has to do with uncertainty and gaps in the records, which—it bears repeating—are pervasive. Moreover, not all of the information available in the Dictionary was retrieved by the process of datafication. On the one hand, there were case-by-case decisions, such as the early choice not to capture aristocratic titles for which extensive data sets exist already. On the other hand, the omission of the category “unmarried” went unnoticed until it was too late. A category often pursued in prosopographical databases, that of nationality, was also left untouched. What the Explorer is meant to do by making all data available for download is to facilitate additions or transformations to its data structure. Understanding the formalization and categorization that went into creating the Explorer data is the necessary springboard to undertaking additional, specific types of formalization and interpretation down the line, according to whatever interests or questions researchers and readers bring to it.10

The following sections treat each of the data categories that appears in the database, conveying how each category is built, how it is distributed across time or across the travelers’ entries of the database, and how it can interact with other categories. After sections about the foundational categories of Entry ID, entry origins, and gender, the following sections are grouped under the rubrics of “biographical data” (concerning the lives of travelers), “indexical data” (concerning the connections between entries by way of shared citations and shared mentions of people), and “travel data” (concerning the journeys of travelers). The thread of women travelers, particularly hidden figures, previously subsumed under other entries, is highlighted throughout, as this is the most significant change resulting from the transformation and augmentation the Dictionary’s printed words into the Explorer’s data.

Entry ID

The Entry ID is a numeric data point expressing the unique identifier assigned to each traveler entry and connecting all data pertaining to it. The Entry ID remains constant throughout the database and its exported file formats. It is thanks to the Entry ID that one can confidently move across different fields, filters, and data categories in the Explorer and manipulate data from downloaded JSON or tabular files without losing track of which travelers are being considered.

The data for Entry ID is complete, meaning that there is an Entry ID for each of the 6,007 entries. This is because the Entry ID is a value that was designated when the digital entries themselves were created during the course of the project. But the integer numbers for Entry IDs run only as high as 5,290 (some integer numbers are missing, and there are over a thousand Entry ID numbers with decimal points). These discrepancies bear marks of the longer story of how the entries in the Dictionary were transformed into entries in the Explorer database. The total sum of entry headings identified by parsing in the original print Dictionary came to 5,290. But some of these were simply headings without body text, existing only as cross-references to other entries. The Entry IDs for these “empty” entry headings were deleted, leaving some integers missing (although the information these headings contained was preserved and formalized as alternate names). Other integers that are missing are those originally assigned to Dictionary headings that turned out to refer to multiple travelers. These shared headings were split into singular entries for each traveler, who was then assigned an individual decimal value appended to the original whole number Entry ID. For example, the Dictionary’s heading “Belscher, Mr and Mrs” and its corresponding Entry ID 354 were deleted; instead, the Explorer contains two headings and entries: “Mr Belscher” is Entry ID 354.1, and “Mrs Belscher” is Entry ID 354.2. Other decimal Entry IDs belong to hidden figures—that is, the travelers subsumed within another’s travel entry in the original Dictionary and lacking any heading of their own. For each of these, a new heading and Entry ID were created, the latter represented as a decimal value appended to the original entry’s ID. For example, the entry for the Hon. Aubrey Beauclerk (1740–82, travel years 1778–81) spawned three additional entries: Catherine Ponsonby (1742–89, travel years 1778–81), who was Beauclerk’s spouse; and their two daughters, Catherine (d. 1803, travel years 1778–81) and Caroline Beauclerk (d. 1838, travel years 1778–81). The Entry IDs for these three women in the Explorer are 318.1, 318.2, and 318.3, respectively.

But there are exceptions. The logic of the Explorer’s Entry ID is numerically progressive (just like the alphabetical one of the Dictionary). And it operates with the expectation of a one-to-one correlation between number of travelers and number of entries. This is why when new entries were created— when subdividing headings from the Dictionary that referenced multiple travelers, and when identifying additional travelers among the hidden figures subsumed in existing entries—their new Entry IDs were decimal numbers based on that of the original entry. There are two exceptions to keep in mind. First, a few decimal numbers resulted from a parsing mistake rather than through the intentional process of individuating travelers. During the initial computational “chunking” of the entries, a few headings were not recognized as separate, unrelated entries. These were then split and assigned individual decimal Entry IDs. But unlike the previously explained decimal Entry IDs where there is some connection between individuals who share the same ID number before the decimal point, these entries are unrelated save for this parsing error. By the time this became clear, it would have been too complicated to rerun the parsing correctly; so these remain with decimal Entry IDs in order to preserve their alphabetical order of appearance as in the original Dictionary. Second, some entries in the Explorer do not pertain to one individual traveler. Just like in the original Dictionary, these are instances when a single last name heading contains miscellaneous, sparse information: fragmented records of travelers with that surname at (more or less certain) given times in various locations. An example is the entry for Gordon, which contains sixteen tours, the first in 1704 and the last in 1797—but it is hard to believe that the Gordon who quarreled with a British painter in Rome in the summer of 1704, as reported in Shrewsbury’s journal, is the same who the Wynnes found very amiable in Florence in the summer of 1796, as reported in the Wynnes’ family diaries. The date span makes it unlikely that all these travel records belong to the same, singular traveler named Gordon. Because there is no other way to resolve this ambiguity with currently available information, these entries are maintained just as they were in the Dictionary in the hope that they will have future utility if additional knowledge emerges. (This is the same reason Sir Brinsley Ford and his collaborators included these cases in the archives and then the Dictionary originally.)

Entry Origin

This string data point explains the origin of each digital entry, with three options: “From the Dictionary” indicates entries reproduced directly from the print Dictionary; “Extracted from heading” means newly created by dividing an entry whose heading in the print Dictionary included multiple travelers; and “Extracted from narrative” means newly created by retrieval from the narrative of another traveler’s entry (i.e., hidden figures). This information is variously expressed in words, graphic elements, and visualizations in the Explorer. The Entry Origin dot chart offers a general view across the whole data set showing whether the entries were newly created for the Explorer or already existed in the Dictionary. The decimal Entry ID number is a quick giveaway of newly created entries; moreover, in the Explorer’s individual entry pages, a newly created entry is recognizable by the fact that the traveler’s name appears in yellow instead of black (the standard color used for travelers from the original Dictionary’s headings). Just below the newly created traveler’s name, square brackets indicate the original heading from which the new entry was retrieved. For the newly created entries for hidden figures, the bracketed original heading has a link to the relative entry of origin. While entries for hidden figures contain no body text, an inset box explains the rationale for their creation: to bring visibility to previously subsumed travelers, as well as to highlight the act of recovery.

This Entry Origin information is also available in the data downloaded from the Explorer, in the “Travelers” table under the column “origin.” In the case of entries for hidden figures, the adjacent column “originEntryID” gives the Entry ID of the travelers from whom the new entry was retrieved. The next column, “originEntryName,s” gives the original heading, in full, for the new entries created by the splitting of a multiple-person heading.

Gender

This category tags each entry as string data: “female,” “male,” or “data not available.” This string data is complete in that it has been filled in for all 6,007 traveler entries. This is not surprising given that this is a category constructed and attributed in the course of formalizing the entries from the Dictionary into Explorer data. Completeness, however, does not equate to certainty or ease of categorization. Miriam Posner’s powerful words in 2015 about the crudity of gender binary categorization in data sets have resonated during the construction of the Explorer database and are only reinforced by the more recent writing of D’Ignazio and Klein in Data Feminism (2020).11 Much like D’Ignazio and Klein describe with regard to the binary gender categorization for the Colored Conventions Project, the reason for maintaining this categorization is the context of the records and the intention of the research, where a major priority has been to recover the women whose presence on the Grand Tour has long been obscured.12 The records through which the erasures have taken place, from eighteenth-century archives and accounts to the headings of the Dictionary, counted gender as binary. This was a world in which women were not allowed many of the rights granted to men. The data itself shows this, for there are almost no records for women or their occupations and education. In this context, recovery happens by recounting the women.

There remains a risk of missing records and misattributing categories in the data creation process. It is humbling to remember that it took four mistaken attributions, with the first four all being men, to establish Katherine Read as the painter of the conversation piece British Gentlemen in Rome, which opens A World Made by Travel. How many mistaken records are in the archives and reflected in subsequent readings of them? Careful counting is as hard now as it was then. The advantage of a structured database is that once it is downloaded, anyone can alter the categories as they wish, and I look forward to a future in which we will have more nuanced representations of gender identity for travelers in this data set.

Biographical Data

Traveler Name

Travelers’ names in the database vary from cases of a single surname to multiple names, sometimes including titles and other terms. This is all string data. There are 6,598 records of names for 6,007 travelers. This discrepancy points to travelers with multiple recorded names, labeled in the database as “alternate names.” The original rationale for these alternate names is explained in the Dictionary’s “Note on Method” by Ingamells, who explains that entry headings register the traveler names at the time of their tour, while names acquired afterward through succession to family titles are listed as references on the pages where their alphabetical order places them.13 The print Dictionary contains 279 of these cases. In the Explorer database, these acquired names are recorded as alternate names for these travelers, all of whom are males. Ingamells’ “Note on Method” does not mention, however, the case of twelve women travelers who also possess distinct reference headings because of a marriage-related name change. Indeed, marriage is the reason for most of the remaining three hundred newly created alternate names records in the Explorer data. All but seven of these relate to women travelers recovered as hidden figures from under the heading of their husbands’ entries; for these women, both their maiden and their married names are recorded.14 In the Explorer, all names, including alternate names, can be searched in the “traveler name” field. When downloading the data, the main names are recorded in the “name” column that appears in all three tables—to make it easier to know which travelers are being viewed—while alternate names are listed in their own column solely in the table “Travelers,” which is dedicated to basic biographical data.

The inclusion of alternate names within the Explorer data structure is facilitated by Entry ID numbers, the organizing principle that identifies and distinguishes among travelers and their data. Entry IDs also allow inclusion of travelers who are all but nameless. Unlike alternate names, these are cases of information scarcity and uncertainty. In lieu of a name, only descriptors identifying a person are preserved, such as someone’s father being described as “a tailor from London,” or another only as their parent’s child, “son of x.” The recovery of hidden figures is accompanied by many such instances in which these descriptors populate the database as name data.

Names are another area where historical information is often uncertain, inconsistent, and incomplete. In the print Dictionary, there is a sole case of an additional reference heading pointing to such uncertainty, when “Britton” is given as an alternative for Bretton. Reading through the entries, though, reveals many similar cases of misspelling or alternate names in the records from which the Dictionary was created, even if they failed to originally generate alternative headings. Several entries in the Dictionary explicitly mention such inconsistencies in the sources; many are due to Italian officials mishandling foreign names, but others also occur in British traveler accounts. These cases, together with the many instances of “possibly” and “probably” that accompany the Dictionary’s names, are reminders of the difficult and painstaking work of identification conducted by the researchers creating the Dictionary.

Other cases indicate intentional fluidity around names. For example, some travelers traveled under aliases. This was the case for elite travelers such as Lord Bute (1713–92, travel years 1768–69) who, just a few years after his demise as prime minister of England, traveled incognito as Chevalier Stuart, and Lady Gerard (d. 1793, travel years 1724–26), who kept herself “conceal’d and does not declare her True name; [the one she uses] is Plummer.” Other travelers concealed their original names to escape past indictments or to run from debt, as in the case of Henry Fisher (c. 1710–after 1768, travel years 1730–86), who assumed the name of Howard but was imprisoned on suspicion of being “the Fisher that committed the barbarous murther upon the body of his friend Mr Derby,” or Davenport (travel years 1703–4), who, when in debt in Rome, is said to have claimed to be Williamson, a moneyed figure in Leghorn/Livorno. These and other stories of name changes—because of adoption, inheritance, and new identities—are told in the traveler lives preserved in the Explorer. These are stories of self-reinvention that are not captured fully by the Names category but that word-searching for a particular “name” brings to the surface.

Birth Date

This four-digit numeric data category is complete for 2,439 travelers (40.6 percent) entered in the Explorer. For around a quarter of these, the years of birth are qualified by word markers that indicate some measure of uncertainty or approximation, such as circa, by, or after.15 These markers are string data; in the Explorer, they are made visible, displayed next to the year of birth in the left column of the travelers’ individual entries. In the tabular download of the data from the Explorer, they are recorded in the column “markers” next to that for year of birth.

When working with the year-of-birth data, grasping its uneven distribution across time is just as important as understanding how complete or uncertain it is. The earliest year of birth for a traveler in the database is 1634, the latest 1806, and both are unique instances: only one person is born in 1634 and only one in 1806. These two are outliers: most of the travelers (93 percent) were born between 1677 and 1777, and most years between 1730 and 1770 register between twenty-five and forty records each. Moreover, the individuals recorded as being born in 1634 and 1806 are not easily counted as Grand Tourists: the first is the approximate date of birth of a long-term resident merchant in Leghorn/Livorno—Gilbert Serle (c. 1634–1712, years of travel –1704-11)—and the second that of the youngest daughter of a long-term resident and navy commander in Naples—Elizabeth Acton (1806–47, travel years 1806–29). Most of the travelers in the database with the earliest dates of birth are long-term residents, including merchants, diplomats, or members of the Jacobite court. The first to fit the profile of a Grand Tourist—traveling in his twenties with a tutor before accessing his family title—is John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll (1680–1743, travel years 1701, 1711, and 1712), born forty-six years later then Serle. At the other end, most travelers with late dates of birth were born in Italy rather than having traveled there. The latest year of birth for a tourist not born in Italy is that of Lady Caroline Creighton (1779–1856, travel years 1785–90, GTE 1197), daughter of Lady Erne (1753–1842, travel years 1785–90) and granddaughter of Lord Bristol (1730–1803, travel years 1765–66, 1770–72, 1777–79, 1785–86, 1789–90, 1794–1803), who traveled with her mother and grandfather at the age of six. As stated earlier, the overall distribution of birth years across the century reflects a distinct increase in women travelers. Between 1634 and 1700, less than 4 percent of the 480 recorded dates of birth are for females. But this percentage more than doubles between 1701 and 1749, when there are 1,295 dates of birth, of which 9.4 percent are those of females; and finally, between 1750 and 1806, there are 662 records, of which just over 20 percent are those of females.16

Death Date

This four-digit numeric data category is complete for 2,672 of the travelers (44.5 percent). For eighty-two of these, the death year, like the birth year, is qualified by word markers indicating some measure of uncertainty or approximation, such as circa, by, or after.17 And, as for the birth years, these qualifying markers are also string data: the Explorer displays qualifiers next to the death year in the left-hand column of the travelers’ individual entries. In the tabular download of Explorer data, they are recorded in the column labeled “markers” adjacent to the death year. Noticeably, the database contains many more death dates than birth dates, and the death dates appear to be much more certain—622 birthdates have qualifying markers versus only 82 death dates.

Just as when working with the birthdate data, grasping the uneven distribution of death dates across time remains as important as understanding how complete or uncertain the data is. Again, the overall distribution of death dates across the century, considered together with gender data, reflects a distinct increase in women travelers. Between 1701 and 1749, of the 443 deaths recorded, less than 5.87 percent are females. This percentage more than doubles between 1750 and 1806, when there are 1,378 death dates, of which 12.6 percent are female; and finally, for the 851 death dates after 1806, just over 16.5 percent are females.18 Looking closer at the earliest dates of death, at the beginning of the century there are twenty-six deaths recorded before 1710, and all are men—many long-term merchants and military men for whom there is no birthdate, so it is not possible to gauge their age. A few do fit the typical profile of Grand Tourists—traveling after attending a Cambridge or Oxford college for an educational Grand Tour—who died young. The two sons of the poet Dryden, John (1667/8–1703, travel years c. 1692–1703) and Charles (1666–1704, travel years 1692–1703), traveled to Italy, mixing Catholic passion and Grand Tour interests, and both died young from accidents—John in Rome and Charles back home in England. Charles Perrott (c. 1677–1706, travel years 1704–6) died of a sudden illness in Venice. Looking at the end of the century, the travelers with the six latest death years (spanning 1861 to 1873) include three women, and the latest recorded death year of 1873 belongs to Mary Anne Acton (1786–1873, travel years 1800–1811), who was the mother of Elizabeth Acton, referenced previously as the traveler with the latest recorded birth year in the Explorer data.19

Flourished

For some travelers the print Dictionary does not give dates of birth and death but, instead, includes years of “flourishing”—amounting, it seems, to years of known activity—indicated by the abbreviation fl. This numeric data exists for sixty-three travelers; nine of the given years are accompanied by markers of uncertainty in string data form (“c.,” “?,” “late,” “after”). For five travelers, only a single year of flourishing is given, but for the remaining travelers, their flourishing years are expressed as a time span; of these, the widest time span is fifty years of flourishing for John Panzetta (fl. 1780–1830, travel years –1787), and the shortest span is three years of flourishing for William Parker (fl. 1722–25, travel years 1722–25). The Explorer displays years of flourishing under “flourished” in the left-hand column of the travelers’ individual entries. This data is not actionable in the Explorer, nor is it downloadable in tabular form from the Explorer; however, it is included in the data sheets in the Stanford Data Repository files.

Birth Place

Placenames for where travelers were born range in specificity from town name to the name of an entire country. This is string data, appearing as words in the Explorer display and in the downloaded tabular format. Birthplaces are sparsely known and recorded in the database; there are only eighty-four unique locations accounting for 132 travelers’ births, meaning just over 2 percent of the Explorer’s travelers have birthplace data recorded. The number is too small to make any generalization, but within this small set, around half are locations in England, Ireland, or Scotland; a quarter are in Italy; and the rest span Europe, North America, and South Asia. The top five birthplace cities recorded are in Italy, England, and Ireland: eleven travelers were born in Rome, Italy; nine in Dublin, Ireland; eight in London, England; six in Leghorn/Livorno, Italy; and five in Florence, Italy.

The Italian births include both children born to elite travelers journeying through Italy and children born to long-term Italian residents such as painters, architects, or diplomats. Among the travelers born in locations outside Italy, England, and Ireland, one finds American painters who traveled to Italy for their Grand Tour from Philadelphia. Other birthplaces point to how the British Empire and the Grand Tour are entwined; records show young men born in the Caribbean and in India—the children of enslavers, plantation owners, and colonial officers—who traveled back to England to attend Oxbridge and then take the Grand Tour in the educational tradition of elites. Other foreign births tell stories of work travels, of merchants and entrepreneurs who set off from Britain and settled as far away as Smyrna, Göteborg, or Russia. In these far-flung locations, for example, were born the architect William Chambers (1723-96, travel years 1750-55) and Grace Barker (travel year 1791)—respectively to a British and a Scottish merchant—and the painter Alexander Cozens (1717-86, travel year 1746)—to a British shipbuilder.

Of the 132 travelers with recorded places of birth, twenty-three are female (the large majority of which, seventeen, are hidden figures). Although this is barely above the overall percentage of female travelers in the Explorer data altogether (17.1 percent vs. 15.9 percent), it is notable because in general, the data points for women are much scarcer than those for men. Yet when one compares the places of birth for men and women travelers, distinct differences emerge. For women, most of the recorded birth places—sixteen of twenty-three—are for Italian locations, while for men that number decreases to only 11 out of 106. Even considering just the women with original entries in the Dictionary (six out of the twenty-free), half of them have Italian birth places. Overall, this shows how the women who entered this world of the Grand Tour—and the Explorer database—were neither typical Grand Tourists (elite men whose birth place is recorded alongside rich data in education and occupation) nor artists (with few noticeable exceptions, such as Read, who is one of the six original entries with birth place recorded). But they were also actively embedded in long-term exchanges between Italy and England, with vital links through marriages and long-term stays, which manifests in the data in this distinctive way. To explore this data further, note that the Explorer displays birth placenames in the left-hand column of individual entries, and that it is included in the tabular data download.

Death Place

Like places of birth, geographical locations where travelers died range in specificity from town names to country names. This is string data, appearing as a search field on the Explore page, as well as in words in both the Explorer entries’ display and the downloaded tabular format. Places of death are sparsely known and recorded in the database; there are only seventy-one unique locations accounting for 320 travelers’ deaths, meaning just over 5 percent of the Explorer’s travelers have recorded death-location data. Again, the number is too low for generalization, yet one readily sees that more travelers die in Italy than are born there: while a quarter of the recorded births were in Italy, more than 80 percent of recorded deaths are in Italian locations, while less than half of the placenames recorded are in Italy (thirty-two out of seventy-one). The top five cities where traveler deaths are recorded are all in Italy: Leghorn/Livorno, with seventy recorded deaths; Rome, with sixty-seven; Naples, with forty; Florence, with twenty; and Venice, with sixteen. Of the thirty-nine death locations outside Italy, ten are in the British Isles, six in British colonies and outposts, and the remainder spread across Europe. Of all these non-Italian locations, six places have two death records each, while the rest have only one.

When considering gender, there are sixty-four women with records of place of death, of which twenty-two are newly created entries. We have records of place of death for women travelers at a higher rate than for men (6.7 percent vs. 5.11 percent), which is striking when, in general, data for women is scarcer. But also striking is that Italian places dominate even more the records of women than those of men (67.18 percent vs. 58.82 percent), pointing to deep Italian affinities in these women’s lives. At the same time, though, only twelve different locations are recorded for women, while twenty-eight are recorded for men. Besides the shared best-known locations (Leghorn/Livorno, Rome, Naples, Florence, Venice, Pisa, Palermo, and Milan), the records for men also include other well-known cities (such as Genoa or Turin) that do not appear in the women’s records, as well as many more remote places that point to more extensive and varied travel. Even in this small sample of data, there are questions about gender and mobility, as well as gender and recording, that call for further exploration.

Parents

This data gives the names of the parents of travelers when recorded in the database. The database contains this information for around 40% of the travelers. There are 3,110 records for 2,462 travelers, meaning that for 648 travelers, two parents are recorded. For almost a third of these records (1,151) there is an Entry ID, meaning that these parents are also travelers in the database. In some cases, the data includes additional information retrieved from the Dictionary. For 1,323 records, the order of birth is recorded, expressed as a numeric value or as abbreviations: “e” for elder, “o” for older, “yr” for younger, and “yst” for youngest. In other cases, other notations are recorded: “surviving” (228), “heir” (54), “illegitimate,” (25) and “posthumous” (3).

Out of the travelers with parent data, almost a fifth (444) are women, and of these women the great majority—303, that is, almost 70%—are hidden figures. This not surprising, given that many of these women’s presences were recovered through family relations. Yet this data also shows that among the entries for women in the Dictionary, a large majority had records for their parents. There are thus complexities around who is counted and in what terms, but also a clear indication that more needs to be done to understand family connections on the Grand Tour in relation to women.

Marriage

The database contains marriage information for around one-third of the travelers. This data consists of a spouse name, the marriage year, and (when a traveler remarried) a sequence number. This clearly defined tripartite structure varies greatly. What is preserved and recorded of the spouse names might include forename, surname, and title, or sometimes just a forename or, in a few cases, not even that—we only know there was a marriage. The marriage year is absent for a quarter of the records and, in a few instances, is accompanied by qualifiers showing uncertainty. In five cases, neither the spouse’s name nor the marriage date is known but, rather, mere confirmation that the traveler married at some point.20 Of the 2,011 travelers whose marriages are recorded, 272 married a second time and 31 a third time. “Marriage” is not a search field on the Explore page, but marriage data is displayed in the individual traveler’s entry when known, showing the spouse’s name followed by marriage date in parentheses. Where spouses also have Explorer entries, their name appears in blue font as an actionable link. Multiple marriages appear in subsequent rows, one under the other. As downloaded data from the Explorer, marriage data appears in the “Travelers_Life_Events” table among other life events, with the marriage sequence number listed in the column labeled as “eventsDetail1,” the spouse name in the next column labeled as “eventsDetail2,” and the marriage year in the column labeled as “start date.”

Understanding women’s presence in this marriage data better reveals how they feature in A World Made by Travel. Of the travelers for whom marriage data is known, 596 are women. This means that, proportionally, marriages are recorded in the Explorer data for many more women than men (29.7 percent of the marriage data concerns women, who make up only 15.9 percent of travelers). This is less surprising when considering that many women have become visible in the database precisely because of their married status; in fact, of the 640 women with marriage data, 130 records are hidden figures, recovered from the entries of their spouses’ entries. The marriage-status question persists, though, for the thirty-two women in this data set with an original Dictionary entry: did these women travel before or after marriage, alone or with their spouse?

DBITI Employments & Identifiers

These are the terms in the Dictionary that describe travelers’ endeavors, achievements, interests, and defining characteristics. They are listed after the traveler’s name and any recorded biographical dates but before any further biographical information. Around one-sixth of the travelers in the Explorer have these brief descriptors; 914 travelers share 212 terms, and many have two, three, or even four such identifiers. This string data is searchable in a dedicated field on the Explore page, and it is also displayed in individual entries as a blue, actionable link leading to other travelers sharing that term (that is, clicking on William Kent’s DBITI Employments & Identifiers data on “architect” lists the others with the “architect” identifier). In the downloaded data from the Explorer, DBITI Employments and Identifiers data is found in the “Travelers_Life_Events” table in the column for “eventsDetail2.”

This data appears simple in that it consists only of basic terms. Its complexity, however, resides in understanding its pervasively nonsystematic nature. The terms that appear in this data set are both specific and repetitive, with slight variations, privileging the unique over the categorical. This reflects the richness and variety of the writing in the Dictionary. DBITI is the abbreviation for Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy and is meant to remind readers that this information comes directly from the Dictionary, with no further formalization. Here, though, is an attempt to organize the employments and identifiers terms, while also giving a sense of their breadth and variety:

-

Descriptors can include the travelers’ professions, the means by which their lives were defined and sustained. These range from “actor” to “diplomat,” “statesman,” “inn-keeper,” and “impresario.” Sometimes they can be as specific as “architectural publisher” or delineate specialties or type of goods, such as “timber merchant,” “textile merchant,” or “wine merchant.”

-

They can express a defining moment or achievement in travelers’ careers. Examples include “bishop” or “editor of Shakespeare.”

-

They can indicate a defining passionate interest, such as “bibliophile,” “collector,” “patron,” as well as various labels, such as “amateur architect,” “amateur artist,” “amateur musician,” and “amateur painter.”

-

They might offer a personal characteristic, such as “eccentric,” “hedonist,” “miscreant,” or “bon vivant.”

-

They can be an identity—whether national, political, or religious. Examples include “American,” “Scottish,” “Catholic,” “Jacobite,” “Dominican,” and “Jesuit.”

The descriptor data maintains any original alternative spelling, such as “antiquarian” and “antiquary,” or “dilettanti” and “dilettante.” Variations abound; for example, a few travelers are described simply as “writer,” but many more are listed with variations on this category: “agricultural writer,” “author,” “biographer,” “dilettante poet,” “dramatist,” “essayist,” “historian,” “historian of art,” “journalist,” “literary scholar,” “man of letters,” “military historian,” “miscellaneous writer,” “mystical writer,” “novelist,” “occasional writer,” “pamphleteer,” “playwright,” “poet,” and “poetaster.” This dazzling variety is a reminder of how illuminating the DBITI Employments and Identifiers data can be as a means to enter the world of eighteenth-century travelers to Italy; it also indicates that one should explore them in full rather than relying on any individual result to offer systematic insight across the database. As for women, DBITI Employments and Identifiers data is particularly sparse. Only 26 of the 914 travelers with this data are women (2.8 percent), six of them with two terms each. But for four exceptions (“hotel keeper,” “barmaid,” “Jacobite,” and “courtesan”), all the identifiers for women pertain to the visual and performing arts.

Education

The database contains education information for 1,202 travelers, around one-fifth of the total. In most cases, it indicates primary and secondary schools, colleges, universities, or other specialized institutions (whether religious, legal, or artistic). At times, it includes degrees obtained and dates of attendance. There are also cases of travelers studying under specific teachers or apprenticing with specific experts; most often, this is the case for artists and architects. In some cases, only the education location—given as the city or the country—is recorded. This education data is structured around the categories of “Institution” (there are 107 institutions for 1,639 records), “Place” (there are sixty-nine places for 1,734 records), “Degree” (146 records), “Teacher” (ninety-six teachers for 123 records), and “Date” (1,147 dates, given as years of attendance or of degree attained). Under “Education” on the Explorer’s Explore and Search pages, there is a field in each to search for institution, place, teacher, and degree. On individual entries, the educational institutions, places, degrees, and teachers are listed in blue font as actionable links, whereas dates appear next to relevant data in parentheses in nonactionable black font—all in a single line. When downloaded in tabular format, this data is accommodated in the “Travelers_Life_Events” table; following the column “Life_Events” is “Education,” with teacher or degree placed in the “eventsDetail1” column, and the institution in the “eventsDetail2” column, followed by the place and date when recorded.

The institutions appearing under this category represent a variety of British grammar and public schools (Eton and Westminster are the most represented, with 199 and 141 records, respectively), including some no longer in existence, such as Newcome’s School and Shackleton School. Most Cambridge and Oxford colleges are represented—Cambridge with 307 records and Oxford with 439. All four Inns of Court for the study of law have data—Lincoln’s Inn with sixty-three records, Middle Temple with forty-two, Inner Temple with thirty-four, and Gray’s Inn with twelve. The data covers many art schools, as well: the Royal Academy Schools, founded in 1768, with forty-four records; the Dublin Society Schools of Drawings, founded in 1746, with twelve; and the Trustees Drawing Academy in Edinburgh, founded in 1760, with three. Some earlier, more ephemeral, art schools are also recorded: di Graffiani’s Academy, Duke of Richmond’s Cast Gallery, the Foulis Academy of Fine Arts, Fournier’s Academy, Grisoni, Great Queen Street Academy, Shipley’s Art Academy, St. Martin’s Lane Academy, and Vanderbank’s Academy. Travelers are recorded as having attended a number of universities outside of England, including in Ireland (Trinity College Dublin), Scotland (Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and St. Andrews), France (Sorbonne), Germany (Göttingen, Leipzig), the United States (Harvard, Yale), the Netherlands (Leiden), and Switzerland (Geneva). Finally, travelers attended Continental Catholic schools (Douai, St. Omer College, and Saumur) and military academies (Angers, Caen, Fontainebleau, Turin, and Vaudeuil). Teachers under whom some travelers (artists in most cases) studied or trained outside of an institution include famous names and travelers themselves, such as Benjamin West, Joshua Reynolds, and William Chambers. But teacher data also includes some obscure names, or the mere notation “his father,” all of which are preserved in the data as such. These educational records reveal institutional stories as well as individual ones, some that span nations.

They tell, too, of a world that is almost exclusively male. The only educational record for a woman belongs to Katherine Read (1723–78, travel years 1751–53), documenting her education under Quentin de la Tour, Paris (1745). Her Dictionary entry reveals that she was regularly accompanied in Italy by the Abbé Grant since “no unmarried woman is seen in the street alone,” and, as a woman, she was not allowed to attend academies, nor was she allowed to visit all the galleries in Naples.

Occupations & Posts

Occupations and posts listed in the Dictionary range from political appointments and honors to trades and crafts. The Explorer data records 256 such positions and professions, for about 25 percent of travelers in the database (1,522 of them). Often the records of these occupations and posts are accompanied by additional information, such as dates or places. Sometimes this additional information consists of details like the names of people for whom travelers worked or titles of books they wrote. Among the myriad biographical data in the Explorer database, this is one of the most varied and rich data sets. It is organized under eleven thematic groupings—an added interpretative layer designed to assist in grasping this variegated data. On the Explore and Search pages, the Occupations and Posts category can be searched either by using these eleven groupings or as a full list. On the individual entry pages, this data is displayed in the left column under the relevant grouping title as a blue, actionable link; dates appear in parentheses in nonactionable black font. When downloaded, this data appears in “Travelers_Life_Events,” following the column “occupation,” with the grouping placed in the “eventsDetail1” column, followed in the next column “eventsDetail2” by the specific occupation or post. Places, names of employers, titles of publication, and dates appear in the next columns. The vagaries of this data are explained in brief below.

The Occupations and Posts group with the most travelers is that of Statesmen and Political Appointees, which counts 887 travelers. Of these, the great majority (703) were members of Parliament, but other posts include appointments at court (including the Jacobite court in Rome), governorships of colonies, and positions in the governing structure of the East India Company. There are also British mayors and, more notably, one president of the newly independent United States. When downloaded in tabular form, posts are listed in the column “eventsDetail2” and followed, when recorded, by dates and location.

The next-most-populated group is that of Army and Navy, with 305 records for 301 travelers. When downloaded in tabular form, the column “eventsDetail2” lists these travelers as either an army or naval officer (247 and 60 records, respectively), followed by the sparsely recorded locations of service (the eight non-British locations include Sardinia, Austria, Russia, and Prussia) and dates.

Under Diplomacy are 402 records for 203 travelers. When downloaded in tabular form, the next column, “eventsDetail2,” is fully filled in and runs the gamut of positions for these travelers in eighteenth-century British diplomatic service. Locations listed under “place/employer/pub” in the next column include the full scope of Italian sites of British diplomacy but also many farther afield in Europe, the Mediterranean, and beyond, reaching as far north as Sweden and east to Constantinople, Russia, and China. Most records also have dates.21

The next-most-populated category is Scholars, Academics, and Authors, with 240 records for 178 travelers, showing a great variety of occupations and posts. The most numerous among these are “authors,” of which there are seventy-one, followed by fifty-two “fellows,” and twenty-eight “professors” of various subjects. The latter two are usually listed together with their institutions of learning, such as colleges, universities, and academies. In the downloaded tabular version of the data, these institution names are listed under the column “place/employer/pub” followed by dates in the subsequent columns when available. For authors, translators, and editors, the title of the works written, translated, or edited appears under “place/employer/pub.”22

The Clergy group counts 296 records for 154 travelers. This discrepancy lies in the nature of a British clerical career, which involved moving from post to post across space and time—all recorded in the Explorer data. For example, an individual might start as a rector at an Oxford college, advance to a number of prebendaries, and end up as a canon at Westminster, all in the course of two decades. Fifty records are for “ordained” travelers, with indication of date but no place. Where recorded, these clergy locations are mostly British, but they also include places outside England—in cities such as Paris, Lisbon, and Leghorn/Livorno. Some clergy were posted at institutions or assigned to households, with postings ranging from the British factory at Leghorn/Livorno to the royal house to other titled families.23

The Artists, Architects, Craftsmen group includes 106 records for seventy-seven travelers. The largest number of records are for architects, with dates of employment in various institutions (foremost of which is the office of Works) but also with individuals. Musicians, visual artists (painters and sculptors alike), and engravers are also well represented, employed by institutions, households, and individuals (including other artists). These employers feature under “place/employer/pub” in the data download. Masons appear in this group—the craftsmen of architecture, employed by the same institutions as some of the architects—as do evocative posts such as the musical director of the theater in Calcutta.

The Law group has fifty-three records for forty-nine travelers. When downloaded in tabular form, all but nine have “called to the bar” in the next column of “eventsDetail2” and have no record of place, but they do have a date for when they were admitted to the legal profession. Most of the remaining records detail judiciary appointments, together with specific locations, all of which are outside England (three in Scotland, one each in Dublin, Bengal, Jamaica, and Pennsylvania).

The Domestic Service group has forty-five records for forty-six travelers. This category includes many of the restored hidden figures whose identities and travels are in the Dictionary but subsumed in the service (and entries) of others and, at times, recorded not with a name but only with the definition of servant. There are also instances of “servants” in the Dictionary’s original entries. This category in the Explorer data runs the gamut from tutor and governess to attendant. A disconnect exists in the name for this category—how can “domestic” refer to a traveler?—but it underscores also the particularity of these positions in the world of travelers, these individuals who were all the more essential in nourishing the intimacy of a home while on the go. Because of the numerous hidden figures who are disproportionally women, this category numbers as many women as men. Nonetheless, this category remains among the least populated—at the opposite end of the spectrum from the numerous recorded MPs—because it concerns those most susceptible to erasure in the records.

The Finance and Trade group includes forty-one records for thirty-seven travelers. Most numerous in this group are records for merchants, followed by directors and governors, then bankers, and then other trade or administrative positions. When downloaded in tabular from, geographical locations are listed under “place/employer/pub,” be these the cities or regions where merchants and bankers worked (such as Leghorn/Livorno or West India), but also institutions where directors and governors served (foremost the Bank of England). There are also rarer instances of specificity, such as the case of “the manager for the Clives Estates,” manager of the Queen’s Theatre in London, and the “agent for Irish Tourists.”

The Patrons and Founders group counts thirty-two records for thirty-one travelers. The majority (twenty-six) served as trustees of the British Museum. There are three founders (of a museum, a Cambridge college, and an almshouse, all given under “place/employer/pub”) and two patrons (one of an academy and one of an artist, both given under “place/employer/pub”).

The Physicians group includes thirty-four records for twenty-eight travelers. Most are listed as physicians, but there are seven records for surgeons, and one each for an apothecary, an oculist, and a director-general. Data in the “place/employer/pub” column varies; some travelers are recorded as having served in actual locations (Dublin and Aylesbury, for example), whereas others served institutions ranging from hospitals to factories abroad, a boat, or the military forces, and still others served individuals in the Royal House. Dates are available for most records.

The Occupations and Posts category is the most varied in terms of position types. It also encompasses the greatest span of status for travelers, from prime ministers to servants. The category, however, is monolithic in terms of gender. Only ten of the almost 1,500 who have data in this category are women—less than 0.5 percent. Many of the eleven groupings were closed entirely to women, including clergy, diplomacy, law, physicians, and the military. The two most-represented groupings for women are service categories that exist at somewhat opposite ends of the class spectrum: there are two women in Domestic Service (a maid and a governess) and four in Statesmen and Political Appointees (attendants to the queen and princess: a unique sort of domestic service that is here placed among political appointments). Besides these women, there are two more in Scholars, Academics, Authors and one “figurante at the Opera” in Artists, Architects, Craftsmen. That the more famous writers, such as Lady Montagu (1689-1762, travel years 1718, 1739-41, 1746-61), Hester Piozzi (1741–1821, travel years 1784–86), and Mariana Starke (c. 1762–1838, travel years 1792–98), or painters, such as Katherine Read, Anne Parson, and Emma Greenland, do not appear in these Occupations and Posts groups is a reminder of the limits of these categories, as efforts at formalization weighed faithfulness to the Dictionary’s entry structure against clarity and consistency. One will find these other women acknowledged in the DBITI Employments and Identifiers under “writers” and “painters.” Indeed, there one finds as many as 165 painters, which is more than twice as many travelers as those listed in the Artists, Architects, Craftsmen grouping of Occupations and Posts. When searching for specific qualities, attributes, and professions across the travelers, the best practice is to use multiple categories and dimensions—as well as to use the free word search feature.

Military Careers

This category lists the ranks for travelers who served in the military, with 723 records across 265 travelers. This large discrepancy hints at how many travelers with military careers—more than two-thirds of them—held multiple posts as they rose in army or navy rank. In this sense, this data serves as an extension of the army and navy grouping under the Occupations and Posts category, particularly for officers for whom various ranks were recorded. In the Occupations and Posts category, the data expresses whether a traveler served as an army or navy officer, together with dates and places when available (ranging from an actual location name to a regiment or commander under whom they served). By contrast, the Military Careers category lists the traveler’s various ranks acquired together with dates when available. The dates cover the traveler’s initial entry into the military and subsequent promotions in rank—as well as, in one case, a date of dismissal. The great majority of military records concern the British Army or Navy, but in some instances, travelers joined a foreign service; these circumstances are revealed by either the non-English wording of the rank or by the place of service listed in Occupations and Posts. In the Explorer, “military careers” is a search field on the Explore page. The military careers data appears also in the left-hand column of a traveler’s entry, under the heading of the same name; the ranks are listed as a blue, actionable link that opens a list of all other travelers with the same military rank, while the dates are in parentheses in nonactionable black font. When the data is downloaded, it appears in the “Travelers_Life_Events” table in the rows following the “Life_Events” column labeled “military career.” “eventsDetail1” states the branch of service, and “eventsDetail2” gives the rank (spelled out in full rather than the abbreviations used in the original Dictionary entries). The “place/employer/pub” column is always empty, and the dates, when recorded, are given in the next column.24

There are no women in this data set, and it consists of a small sample of travelers (less than 5 percent). Nonetheless, this data set contains significant information density. It raises new questions about the world of travelers to Italy that researchers can begin to approach systematically, such as how military careers correlate with education levels and other professions, or whether travelers with military careers are on the Grand Tour for reasons related to their service. Are they visiting Italy as part of campaigns, intentionally adding a tourist element to their service, or are they simply tourists who happen to have served in the military? The relationship between wars and the Grand Tour has been considered in terms of how wartime disrupted travel, but there might be new dimensions to explore starting from this set of military careers.

Societies & Academies

These are the travelers’ cultural, artistic, and professional associations and affiliations, ranging from music to the visual arts, and from medicine to engineering. The Explorer data contains 701 records corresponding to 501 travelers’ affiliations, with twenty-four different societies and academies. The discrepancy in numbers attests both to the fact that travelers belonged to multiple associations and to the fact that some travelers played different roles at different times within the same society or academy. This data category consists of society or academy names, the travelers’ roles in the given organizations, and the dates associated with each role (when recorded, which is the case almost 90 percent of the time). The most populated associations are the Society of Dilettanti (with 222 records), the Royal Society (with 214 records), the Society of Antiquaries (with 140 records), followed by—after a significant drop—the Royal Academy (with 40 records). Among the roles, “fellow” is by far the most attested (366 records), followed by “member” (248 records). Other roles are much more sparsely attested, such as “associate member” (29 records) and “president” (19 records). A few are unique, such as “leader of expedition to Asia Minor,” “accompanied Dilettanti’s expedition to Greece and Turkey,” and “declined.” Nine of the twenty-four associations are non-English (four Scottish, two Irish, and one each American, Italian, and German). In the data download, this data is in the “Travelers_Life_Events” table with “society” in the “lifeEvents” column, showing the role in “eventsDetail1,” the institution in “eventsDetail2,” and providing the year under “startDate” and “endDate.”

This is another data set within the Explorer that—like military careers—is solely male and that, while small, is information-dense. It is interesting that the great majority of the travelers holding three different records for society and academy associations (twenty-six out of thirty-one) share affiliations with the same three (Society of Antiquaries, Society of Dilettanti, and the Royal Society).

The data for membership in societies can be interrogated in conjunction with member characteristics such as education or social status to explore the largest and smallest numbers of overlaps, who the outliers are, and so forth. It is vital while exploring this data to consider the lifespans of these societies and academies. To ensure comparison of comparable data, take into account that different societies were founded at different times, and some did not exist throughout the eighteenth century. Here is a list of the twenty-four associations in descending order of their membership numbers in the Explorer data, along with dates of establishment: Society of Dilettanti (222 travelers, est. 1734); Royal Society (214 travelers, est. 1660); Society of Antiquaries (140 travelers, est. 1717); Royal Academy (40 travelers, est. 1768); Architects’ Club (11 travelers, est. 1792); Royal College of Physicians (10 travelers, est. 1518); Society of Artists (8 travelers, est. 1760); Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (3 travelers, est. 1780); Royal Society of Musicians (2 travelers, est. 1738); Society of Virtuosi of St. Luke (two travelers, c. 1689-1743); and Free Society of Artists (2 travelers, 1761–83). Associations with only one traveler affiliated: Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (est. 1681); Royal Society of Berlin (est. 1700); Hell-Fire Club (c. 1730s–60s); Royal Medical Society Edinburgh (est. 1734); Society for the Encouragement of Learning (est. 1735); American Philosophical Society (est. 1743); Royal Society of Arts (est. 1754); Society of Civil Engineers (est. 1771); Society for Promoting the Arts in Liverpool (1783); Royal Irish Academy (est. 1785); British and Foreign Bible Society (est. 1804); Old Water Colour Society (est. 1804); and Royal Hibernian Academy (est. 1823).25

Exhibitions & Awards

These are records for the art exhibitions in which travelers displayed their work, as well as for any prizes and educational fellowships they were awarded. There are 419 records for 147 travelers. The data consists of the institution names that hosted exhibitions and granted prizes and fellowships, as well as any specific awards received. There are ten institutions and forty-five awards granted. Dates are also included in the data when known, and they pertain to either exhibit or award years. By and large, these records concern visual art, but there are also a few traveling scholarships given to doctors, scholars, and artists. The Explore and Search pages have two different search fields listed under the Exhibitions and Awards category—one for the institution, and one for the award type. In an individual traveler’s entry, these fields are combined, separated by a comma, and both appear as a blue, actionable link leading to the list of travelers who share the same exhibition or award. Dates appear next to relevant data in parentheses in nonactionable black font. In the data download, this data is in the “Travelers_Life_Events” table with “exhibition” in the “lifeEvents” column, showing the institution or award in “eventsDetail2” and providing the year under “startDate” and “endDate.”

By far the most populated of the ten institutions is the Royal Academy, where 120 artists exhibited. With such overall small numbers, though, what is perhaps most notable is the representation of a diverse set of institutions. Moreover, four women artists are represented in the records: four exhibited at the Royal Academy and one of these four, Katherine Read, exhibited earlier at the Society for Artists and at the Free Society of Artists. Both the exhibitions and the traveling scholarships were deeply entwined with the Grand Tour: artists displayed works made in Italy, and the traveling scholarships were essentially dedicated to learning while traveling in Italy.

Indexical Data

Sources

These are the records for sources referenced in the entries, consisting of published titles and archival material, that appear in the Dictionary’s footnotes and extensive bibliography. There are 545 sources, and a majority of entries (69 percent) reference at least one. The most commonly referenced sources are archives: appearing in 677 entries, the State Archives in Venice are the most referenced, due mainly to the Note dei Forestieri, which records visitors coming to and leaving Venice in the eighteenth century. The second most referenced, with 641 entries, is the 1931 publication of the University of Padua’s visitor register, and the third, with 405 entries, is the published Walpole Correspondence.26 Archival and manuscript material—whether published or not, public or private, Italian or British—represents the majority of sources, along with some eighteenth-century published traveler accounts. Some secondary literature is included, but it is important to remember that it dates at the latest to the 1990s. Much has been published since, as the Dictionary itself, published in 1997, spurred many later publications.27

Women are underrepresented overall among entries with sources, counting for only 6.5 percent (while overall in the database they represent 16 percent of entries). This is not surprising given that hidden figures entries are less likely to have sources. It is interesting, though, to consider these numbers with respect to individual sources, starting with the most cited ones. In the Venetian Note dei Forestieri, women account for 10 percent of the citations; in the records of the University of Padua, they account for less than 1 percent (three out of 641); in the Walpole correspondence, they account for 11 percent. It would be worthwhile to explore further how much the archival records differ from personal accounts in mentioning women.

This data appears in abbreviated title form in the search box for sources on the Explore page. On each entry page, the data appears in abbreviated form in the left-hand column under “Sources”; hovering the cursor, though, displays the full source title. A quotation mark appears beside the data as a blue actionable link leading to a list of all entries sharing the same source. In the tabular download, this data appears in the “Travelers” table in the “Sources” column in abbreviated form and separated by commas. This data consists of bibliographical information, which, formalized as data, gives some systematic insight into the construction of and connections within Dictionary content. This data allows new ways of interacting with the entries online while offering additional information when downloaded for further work.

Mentioned Names

These are the records of people mentioned in others’ entries. More than four-fifths of the traveler entries have at least one mentioned name. There are 24,234 records for mentioned names, totaling 6,502 unique names. Of these mentioned names, 4,323 are other travelers with an Explorer Entry ID. The top three most mentioned names are Horace Mann (1706-86, travel years 1732-3), who is mentioned in 426 entries; Sir William Hamilton, who is mentioned in 243 entries; and the Italian painter Pompeo Batoni, who is mentioned in 209 entries. Batoni, as an Italian, does not have an Entry ID. Of the top ten most mentioned, three are non-British and thus lack an Entry ID: following Batoni are Stosch (158 entries) and Cardinal Albani (114 entries). To find a woman, users must scroll down to two painters, both non-British and with no Entry ID: at number twelve on the mentioned names list is Angelica Kauffman (mentioned in ninety-eight entries), and at number fifteen is Rosalba Carriera (with eighty-seven mentions). The first woman traveler with an Entry ID listed is Lady Montagu at number nineteen (with seventy-five mentions).

Most of the mentioned people without an Entry ID remain unidentified, but they serve as a reminder of the richness of the world of travel encountered by the British and Irish in Italy. In the Explorer, the mentioned names are displayed on both the Explore and Search pages, as well as on the individual entry pages. On the Explore page, in the search box that lists all mentioned names, the names of mentions without an Entry ID are marked by an asterisk. For each traveler entry, this data appears in the left-hand column. Mentions with an Entry ID are listed in black mouseover text displaying a preview of their entry, followed by a quotation mark as a blue actionable link leading to a list of entries sharing that mention. Mentions without an Entry ID are listed in black italic font. In the tabular download, this data appears in the “Travelers” table divided into two columns: the “mentionedNamesWithEntryID” column contains names with an Entry ID, while those with no Entry ID are in the column “mentionedNamesWithNoEntryID.” In both cases, the full names are given, separated by commas. An additional column, titled “IDmatchesForMentionedNamesWithEntryID,” contains all the Entry ID numbers, separated by commas.

Travel Data