I. Entering a World Made by Travel: Introducing the Explorer

I. Entering a World Made by Travel: Introducing the Explorer

The New World of Grand Tour Studies

Doing Research with the Explorer: Seven Scholars’ Essays

Behind and Beyond the Canvas

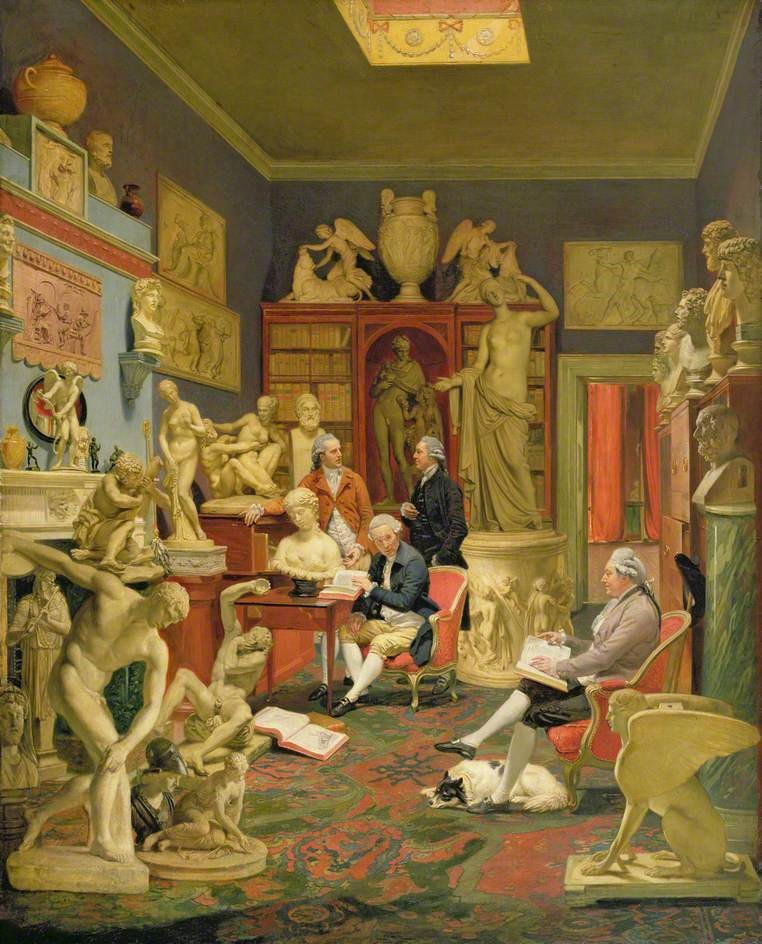

Rome, c. 1751: six elite British male travelers depicted in the distinct conversational style favored at the time for group portraits, with Roman ruins in the background signaling the men’s animated and engaged presence on Italian classical ground (fig. 1). It has long been known who is represented here: the jauntily leaning central figure is Charles Turner, the original owner of the painting, and on his left he is supported by Sir William Lowther. Seated to their left is Lord Bruce, and the figure standing in between is Thomas Steavens (who, as close examination reveals and sources confirm, was added expertly after the others were already painted). On the far left is Sir Thomas Kennedy, talking with the Irish peer of the group, James Caulfield, 1st Earl of Charlemont.1

All these men were indeed in Rome on the Grand Tour in their early twenties, and all belonged to the group, led by Lord Charlemont, that sponsored the establishment in 1752 of an academy in Rome to support British artists—a short-lived institution credited as an inspiration for the Royal Academy, founded in London in 1768. Lord Charlemont can be considered the most prominent of the six: he stayed abroad, mostly in Rome, for almost nine years, serving as patron to numerous British and Italian artists, collecting profusely, and socializing with both travelers and Italian notables. He returned home and became a leading political figure of his day while commissioning and championing the construction of various classically inspired buildings that even today mark Ireland’s built environment. To varying degrees, the other five also went on to occupy political positions, join learned societies, and collect and sponsor art and architecture inspired by their tours.

Apart from three minuscule local stock figures in the painting’s background, no others can be seen. Completely invisible are those who made these British Mi’Lords’ travels possible: tutors, servants, and staff, as well as the many others with whom they interacted en route—Britons but also Italians and other foreign travelers and residents. Women are nowhere to be found, although art historians have determined (after four mistaken attempts at attribution) that, ironically, the painting itself was the work of Katherine Read, one of the very few female artists who traveled and worked in Italy in the eighteenth century.2 Both Charlemont and Lord Bruce were also admirers of the musical accomplishments and regular visitors of another woman, the Irish traveler Miss Eugenia Peters. Charlemont, moreover, is attested as having had, at one point during his time in Rome, “four Italian servants, his Irish valet,” and two additional English employees.3 The other five men likewise met, socialized, and traveled with a wide range of people, many also from far less privileged social and economic backgrounds.

More glaring, but also to an extent more identifiable, are omissions today apparent in Johan Joseph Zoffany’s famous painting The Tribuna of the Uffizi, with its more crowded cast of mostly young touring British elites, likewise engaged in the conspicuous consumption of Italy’s classical past (fig. 2). Zoffany shows us a couple of tutors, artists, a diplomat, and a military officer, but again there are no women, no members of the lower classes, and no locals or Italians present but for the director of the Uffizi himself, Pietro Bastianelli, holding the famous Venus by Titian for the visitors’ inspection. Thanks to Bastianelli’s administration, we have archival records for the Uffizi in these years showing that visitors skewed aristocratic and foreign, with the British in the majority. But these same records show that many foreigners’ visits were by women, that a good number toured with Italians as guides or companions, and that more artists came on their own to study and copy works in the collection. The scene would also have included Italians from Florence and other cities and states, and among the Florentines there would have been nonelites, who may have ranged from dancers to cooks, from fishmongers (a certain Baccani pesciaiolo) to anonymous women upholsterers (tappeziera). The Uffizi’s archival records contain specifics for only about half of the visitors, and we can imagine that those who have been recorded are generally the more socially distinguished, but visits to the museum are also attested in servants’ journals that have been recently published.4

Paintings like Read’s and Zoffany’s represent typical portrayals of the Grand Tour. But A World Made by Travel aims to bring to life what lies beyond the canvas. Here it is possible, for example, to assemble and compare rich information about the six elite British men in Read’s painting—their ages at the time of travel, the places they visited and how long they stayed, their educational backgrounds, and snippet accounts of their tours, as well as their appointments and occupations, all of which gives an immediate sense of the variations among the lives of these elite touring companions. We learn also about them after their travels: two died shortly after returning from Italy; of the other four, two are better known for their scholarly attainments, and both in time were elected to the Royal Society and the Society of Dilettanti, but all went into occupations of power and wealth.

At the same time, information about other travelers with whom they associated, and the other 121 travelers known to have been in Rome in 1751 and 1752, is here readily available, recreating an expanded social context. Those most immediately associated with the six travelers may themselves have been members of the elite, but Italian and British artists were their most numerous points of connection (see fig. 3). Also in the mix were some diplomats, who remain important sources of information about the travelers who relied on them during their journeys. The graph in figure 3 reveals connections to even wider networks, which begin to encompass women, as well as tutors and servants who were Italian, British, and Irish.

Reconstructing the interactions and relationships behind and beyond Read’s British Gentlemen in Rome brings us closer to the daily dynamics involved in the making of modern culture, from Charlemont’s sponsorship of art and architecture to the devotion of his traveling tutor (who was rewarded with a lifelong stipend after the tour), from the domestic labors of unnamed servants who made homes for the travelers in foreign places to the women—including Read, Italian singers, and various intellectuals and socialites—with whom these and other travelers interacted.

All this emerges from the Grand Tour Explorer, a new research tool that is at the core of A World Made by Travel. The Explorer’s principal source is the Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy, 1701–1800, compiled from the Brinsley Ford Archive by John Ingamells and published in 1997.5 An archive of archives, so to speak, the Dictionary has a decades-long history of its own. The Explorer recasts this unique prosopographical reference as a dynamic resource with search, browsing, visualization, and other interactive features—including the ability to download information in any number of configurations—that allow researchers to study travelers’ lives and journeys anew. At the same time, it reveals a vast array of previously unknown or overlooked Grand Tour travelers, decentering the elite and well-known by bringing into the story hundreds of women, servants, workers, and Italians not represented among the original Dictionary’s primary headings, even if they appear within its textual entries. Thus, the 4,992 biographical entries compiled by the Dictionary has increased, through the Explorer, to 6,007.

A World Made by Travel aims to share data with scholars and other users both at scale and in response to particular questions, synthesizing a reference work with original research in an interactive online format. Its distinctive contribution is to harness tools and practices emerging in the new field of digital history to transform and enrich our understanding of eighteenth-century, particularly British, travel to Italy—both its historical significance and its continuing influence. More broadly, the project showcases and makes accessible to researchers, students, and the general public the possibilities of digital history in a digital format, as demonstrated through data, maps, interactive visualizations, digitized archival records, original research essays, and other tools that raise new questions and forge new connections with unprecedented granularity. A World Made by Travel poses a set of evolving answers to the question of what it means to do historical research digitally, in particular with historical data concerning thousands of lives.

* * *

The Grand Tour at the heart of A World Made by Travel is that of British travelers journeying to Italy. As Britain’s global reach spread during the course of the eighteenth century, more and more Britons undertook this travel. Exact numbers are hard to come by, as there is not a single archive for British travelers to the Continent, but estimates put the number at more than ten thousand per year.6

The eighteenth century has indeed been hailed as the golden age of the Grand Tour, but it is important to remember that Continental travel for education, tourism, and art collecting existed well before and after this period. The term Grand Tour itself was coined by Richard Lassels—a British tutor who visited Italy five times with different charges—in 1670, in his immensely successful and long-lasting travel guide The Voyage of Italy, and British elites had traveled to Italy as tourists since the Renaissance. Nor did the end of the eighteenth century see the end of such travel. Although the age of revolutions and the Napoleonic wars certainly disrupted itineraries and practices of Continental travel, these interruptions, alongside changes brought about by technology—including, in time, the steamboat and then the train—deeply transformed travel to Italy. But they did not diminish it; if anything, journeys to Italy grew more frequent and numerous in the nineteenth century, and the transformation into mass tourism was a long and complex one.

Nor was the Grand Tour limited geographically to Italy. Lassels himself recommended the tour of Italy as part of a longer itinerary, debating the merits of touring France, Germany, or Holland on the way to or from Italy. There was of course no direct way to Italy (if not by sea), but it is also true that these other places were destinations in and of themselves, whether Italy was reached or not. Paris saw many more British visitors than Italy, sometimes due to monetary constraints, while others also went beyond Italy, using it as a launching pad for destinations farther beyond in the Mediterranean. Finally, it was not just Britons traveling. Archives tell us as much: the Uffizi’s records, for example, show many French visitors, as well as other Europeans and travelers from other continents, from North America to North Africa.7

A fluid historical experience like the Grand Tour is hard to fit into strict geographical, chronological, or national boundaries. Goethe, a German, visited Italy in the late 1780s but did not publish his most influential account—Italienisch Reise, among whose most vivid pages are those set in that British center of sociability and collecting that was Sir William Hamilton’s house in Naples—until 1816. The Dictionary itself, focused as it is on the British and Irish in Italy from 1701 to 1800, seeps beyond its own margins—something that the computational and data approach makes very clear, highlighting locations outside Italy, dates before and after the eighteenth century, and many people beyond the British and Irish travelers of its title.

While using Grand Tour to refer, in particular, to eighteenth-century British travel to Italy and the sustained conversation that, in the eighteenth century and since, centered it, A World Made by Travel acknowledges this wider context. Indeed, there were nearly as many pathways to Italy, and as many reasons for traveling there, as there were travelers who undertook the journey. A World Made by Travel seeks to honor the variety of people who collectively constituted this distinctive world, while also keeping an eye on the widely shared sense at the time that an Italian journey—particularly when imperial power was shifting from the South toward the North and the West—held the key to becoming a citizen of the world.

For cultural and social elites in the late eighteenth century, that phrase—“a citizen of the world”—succinctly captured the allure of Italy. As the English critic Samuel Johnson remarked, “A man who has not been in Italy, is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see.”8 Dotted with the monuments that elites knew from their reading of the ancient Greeks and Romans, and populated by influential contemporaries who might be encountered in the flesh, the Italian Peninsula promised an educational rite of passage rooted in humanist ideals of classical origin, while fostering the transformation of antiquarian interest for the past into modern practices of knowledge. Every journey, however, involved many other people, including (despite Johnson’s masculine language) women—a fact that highlights important questions about who gets remembered and how their journeys are interpreted.

The story of the Grand Tour of Italy is a story of nations as well as of individuals. As such, it holds enormous cultural and historiographical significance today. To study this transformative historical phenomenon, to think about its participants and recreate their paths, is to encounter an increasingly diffuse learned community whose travels helped shape the modern world as we know it. This was a community of travelers consisting of reluctant youths and intrepid women, of scientists and artists, of the Enlightenment’s most sensitive minds and influential writers, and of many other (mostly unnamed) figures. Among them were diplomats, merchants, sea captains, doctors, governesses, and servants, who made these travels possible and who may not have been seeking an educational rite of passage at all—who, instead, sought professional advancement, or a way to make a living, or who did not even travel by choice. The countless crossing of paths that constituted this world of travel—its multifarious exchanges of material objects as well as ideas and interactions, many planned but as many unexpected—contributed to a massive reimagining of politics and the arts, of diplomacy, of the market for culture, of ideas about leisure, and of professional practices such as archaeology and the teaching and collecting of art.

Yet the Grand Tour, despite being a fundamental engine of modern life, has long posed a considerable historiographical challenge. Our grasp on this phenomenon today is constrained by the widely dispersed documents through which we can study and come to know it. Not that there is a shortage of existing texts. Many travelers kept journals and wrote letters, a number of which were published at the time, and those published “travels” were themselves shaped not just by ancient texts but also by previous travelers’ accounts. Even these texts, however, account for the travels of only a fraction of those who voyaged to the Italian Peninsula in these years. So while the enormous scale of the Grand Tour, with numerous individuals traveling across a vast geography, is well understood today—indeed, this is seen as a crucial feature of its influence—the fact remains that when we define and understand it through the writings of only a small selection of travelers, we barely glimpse its scope.

Written accounts, published or in manuscript, offer merely a trace of the record left behind by Grand Tour travel. Archival records are widely dispersed throughout Italy and Britain, and an extraordinary amount of visual evidence remains, even down to the painted depiction of individual travelers (to have one’s portrait painted in Italy, whether at full scale or in miniature, was a sought-after experience). Such records, though, can suppress as much as they reveal. Because the Italian Grand Tour, a formative institution of modernity, was constituted by the movement of people, relying on only the most well-known accounts and depictions risks ignoring much of its actual life and enormous subsequent impact.

Access to more stories expands the scope of our knowledge, but the act of counting is always tied to decisions about what to count, interpretive acts of categorization, and, thanks to the richly documented and multidimensional character of our data, how different categories intersect. Only thus can the lives and journeys of travelers otherwise hard to ascertain be brought to bear in the same picture and narrative. Data visualization and data analysis allow us to see many more people than before. In this approach, which is committed to the interplay between the qualitative and the quantitative, we can establish a new sensitivity to the unknown players in our historical past. When historians began dreaming, with the advent of the personal computer in the early 1990s, of the new possibilities of processing large amounts of data quickly and easily and of exchanging data sets and information via machines, they could scarcely imagine the ease of today’s file transfers or the dynamic web applications that allow us to zoom in and out from individuals to groups, draw networks and connections, and manipulate categories in our explorations. Yet this exponential computational growth and the advent of artificial intelligence have revealed all the more the importance of careful source and data criticism. To quote Mateusz Fafinski: “Historical data is not a kitten, it’s a saber-toothed tiger” that will undermine any work not attending to its complex uncertainties and missing records.9 A dynamic digital tool like the Grand Tour Explorer opens exciting vistas on and approaches to eighteenth-century British travel to Italy, but doing research with historical data requires as much scholarly attention and care as traditional historical research.

The New World of Grand Tour Studies

A World Made by Travel builds on a tremendous groundswell of exciting scholarly work undertaken in recent decades on the nature and meaning of the multifaceted world of travel to Italy.

For a long time, research on travel was difficult to fit into academic institutions, and it is perhaps partly for this reason that crossover work of interest to a wider public and conducted by independent scholars has filled the gap.10 The elaborately researched surveys by Christopher Hibbert and Jeremy Black, successful as they were in the trade press, also heralded a new academic turn.11 In the 1990s, as interdisciplinarity flourished, Grand Tour Studies reemerged and attracted cultural historians seeking to forge connections among intellectual, political, and art history and bringing sophisticated literary analysis to bear on seemingly mundane travel writings. Exhibitions in London, Rome, and Philadelphia put on literal display the Grand Tour’s potential as a subject of interdisciplinary scholarship, telling its story through paintings, ancient and modern sculpture, and touristic artifacts ranging from prints to painted fans. The lavishly produced and illustrated catalogs of these exhibitions, as well as the edited volumes based on related conferences, brought together scholars from disparate disciplines to provide context and analysis.12 This moment also comenced a season of research, as scholars such as Philip Ayres, Jonathan Scott, Viccy Coltman, Jason Kelly, Ruth Guilding, and Joan Coutu investigated a broad cultural dialogue about republican virtù and neoclassical taste, studying the complex and richly cultivated ideals embodied in the artifacts collected by Grand Tourists: from marble busts of themselves, commissioned in Rome and made to resemble ancient Roman statues, to Greek painted vases used to decorate their sitting rooms, often atop mantelpieces of neoclassical design.13

As an institution, the Grand Tour was established on the original humanist belief that classical education forged modern men. Not all Grand Tourists were seen as manifesting the ideal: Lady Montagu, for instance, lamented the vulgarity of the English youth she encountered, and tutors frequently complained about their unruly charges.14 Other instances of disappointment offer further proof of the paradox, as described in essential works by Chloe Chard and Bruce Redford, respectively, exploring foreign modes of experiencing travel in Italy in general and Venice in particular.15 Melissa Calaresu and Nelson Moe have analyzed foreign representations of Italian decline that situate Italy on the margins of modernity, though they do so in order to interrogate the limits of Enlightenment ideals of cosmopolitanism.16 Others, including Paula Findlen, have unmasked this mediated, imaginary Italy in a way that allows for a clearer view of the vibrant modernity of eighteenth-century Italian culture.17 These penetrating investigations of the Grand Tour’s ideals and cultural dynamics have recently led to a sustained look at the lived reality of the Grand Tour.

John Brewer, in asking “Whose Grand Tour?,” launched an investigation of collecting practices and how they changed across the eighteenth century. He also sounded a clear call to open up investigations of travels to Italy beyond the narratives dominated by wealthy young men.18 What sorts of reactions did different Italian cities elicit from travelers, and how did the travels of women differ from those of men? Questions such as these animate Rosemary Sweet’s recent work.19 A 2012 exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford of items from the cargo of the British merchant ship Westmorland, which was reconstructed as an ensemble thanks to painstaking work on the archival records of its 1779 capture during the Anglo-French wars, put on display a vivid cross-section of the Grand Tour in keeping with this recent scholarly turn. The ship’s contents—including works of art acquired by Grand Tourists, notebooks and personal possessions, and luxury market goods such as silk, olives, and thirty-two wheels of Parmesan cheese—offer detailed insight into the tastes and interests not just of Grand Tourists in general but also of specific travelers. The fascination with such particulars connects some of the most recent work to that of one of the very first scholars to cultivate the Grand Tour in academia, Edward Chaney, whose collected essays painstakingly examined, case study by case study, its various contexts.20

More recent work zeroes in on lived experiences and unexplored or unquestioned facets of the Grand Tour world. Scholars have focused on the places visited before and after Italy, readdressing the significance of travel in countries north of the Alps, given that many who left England did not make it all the way, that those who reached Italy by land spent much of their time in other locations en route, and that Italians themselves sometimes traveled north.21 Other scholars have plumbed archives old and new with great creativity to throw light on what preceded and followed travel in the lives of travelers. Richard Ansell has carefully explored how families strategized about their offsprings’ travel and what the educational, social, and financial outcomes of that travel were through subsequent generations. Sarah Goldsmith’s research on how masculinity was constructed through traveling posits anew the role of the Grand Tour in shaping British elites. Recent work on country houses and libraries—investigating the integration of imported objects, habits, and books in British genteel living—also extends our understanding of the afterlives of travel beyond art collecting.22

Ilaria Bignamini already posed the crucial question of the role of Italians and Italian culture in the Grand Tour in 1996.23 Careful readings of sources have shed light on the Tour’s Italian contexts and on practices of acculturation, from Arturo Tosi’s study of language acquisition to Calaresu’s research on cooking habits.24 Collaboration with Italian scholars has proved illuminating in this respect, from the already mentioned work by Findlen to the joint study by Paola Bianchi and Karen Wolfe of Turin’s academy. The Centro Interuniversitario di Ricerche sul Viaggio in Italia has done remarkable work in the field, and Cesare De Seta’s thesis on the influence of the Italy envisioned by travelers on Italians’ self-image is at the core of the most recent and most expansive art exhibition on the Grand Tour, “Grand Tour: Sogno d’Italia da Venezia a Pompei,” presented in Milan in 2021 and 2022.25 Attilio Brilli has for decades pushed the field forward by bringing his prolific academic research to a broader public, culminating in the multilingual and multiauthored The Grand Tour of Europe.26

Deep dives into Italian archival sources, along with new analyses of well-known travelers’ accounts, have also added original texture and facilitated new disciplinary connections. One example is Brewer’s recent masterful article on the making of scientific knowledge through a study of the local guides taking visitors up Vesuvius, a story which, moreover, in his most recent Volcanic: Vesuvius in the Age of Revolutions, shows the integration of politics, imagination, arts, and sciences engendered by this world of travel.27 Historians of art and of science, and of eighteenth-century Italy in general, have also provided essential new contexts within which better understand travel to Italy in the eighteenth century.28 The image of the Grand Tour has indeed far expanded in scope from the original focus on travel by wealthy young men and on art collecting, as more participants come into view. While Brian Dolan’s work focused on the “ladies’” Grand Tour, more recent scholarship is foregrounding the great variety of possible women’s travel experience. Explorations of nonelite travelers’ and servants’ experiences are also starting to be explored, both by reading anew well-known travel accounts, as in the work of Kathryn Walchester, and by the rare recovery of servants’ travel accounts from the archive, thanks to the research of George Boulukos and Richard Ansell.29

* * *

The original print Dictionary facilitated research that used a prosopographical approach to push beyond the stereotype of the Grand Tourist as male, young, and elite. John Brewer’s field-shaping essay “Whose Grand Tour?” was argued through close reading of the Dictionary, quoting from as many as forty of its entries. In the same volume in which Brewer’s essay appeared, moreover, María Dolores Sánchez-Jáuregui wrote on the neglected figures of governors or “bear leaders”—travel companions to younger, wealthy elite men, who directed their studies, managed the logistics and finances of their travels, and often influenced their collecting choices. Sánchez-Jáuregui was inspired by her research on the Westmorland, the so-called English Prize, whose cargo contained evidence of bear leaders’ activities. But it was the Dictionary that confirmed for her the value and possibilities of the subject and served her as a major source of information for about 174 tutors.

A World Made by Travel pushes even further in this direction of expansion. Although its starting point is the abundance of detail in the Dictionary of British and Irish Travellers in Italy, the Grand Tour Explorer makes it possible to investigate all travelers, despite scarce or uncertain information, including those effectively hidden until now. The Dictionary is animated by an unusually wide cast of characters, which in part is a testament to the eclectic collecting and research interests of Ford and the many who worked with him to build his archive of travelers, but the Explorer increases this cast by more than a thousand, of which well more than half are women.

Beyond the many stereotypically wealthy Grand Tourists, there are entries for students of the arts and resident artists, humanists (whether scholars of manuscripts or antiquities), merchants, military men, diplomats, and Jacobite exiles. The variable length of the entries reflects differences in what is known about individual travelers, both during and beyond their travels. Many of the longest entries belong to familiar figures whose tours are substantively documented, such as Lady Montagu (1689–1762, travel years 1718, 1739–41, 1746–61) and Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803, travel years 1764–1800). Less-famous figures who nonetheless left behind precise documentation of their travels—such as Patrick Home (1728–1808, travel years 1750–51, 1771-77) and the artist Richard Dalton (1713?–91, travel years 1739–43, 1747–50, 1758–59, 1762–63, 1768–69, 1774–75)—also have lengthy entries, as do people who stayed long in Italy. Well-known figures whose tours were neither extensive nor thoroughly documented, however, such as the philosopher David Hume (1711–76, travel year 1748), whose journey ended at Turin, warrant briefer entries.

Finally, there are travelers about whom almost nothing is known. At times only their names survive, and even these might be uncertain (but are still included). This is the case, for example, for a few of the artists mentioned in the crucial and mysterious document known as “Hayward’s List,” which consists of “a gathering of ten octavo-sized pages stitched together” that records in neat handwriting the names and the arrivals of British artists in Rome from 1753 to 1775.30 Taken together, the Grand Tour Explorer’s entries allow A World Made by Travel to present a newly expansive sense of the Grand Tour’s diversity. This is a world much more densely populated than what we see in the individual journals of Grand Tourists or much of the scholarship based on them, yet on that is fully consonant with the findings of recent Grand Tour studies.

The Explorer

Creating the Grand Tour Explorer was a multiyear, multistep, iterative, and collaborative process. Not only the tool but the process itself grew in scale and complexity alongside contemporary technological developments—a story recounted in detail in “Archive to Explorer.” Offered here is an explanation of the nature of the Explorer and the stakes of the transformation it represents from print source to digital data to an online and interactive research resource, as well as an introduction to the new approach that it enables for the study of eighteenth-century travel to Italy.

At the core of the Explorer, as of the Dictionary, is the individual entry. Atomized content organized around the lives of individuals has long been the foundation of prosopographies. The Grand Tour Explorer pushes this principle further than its print source. Where some entries in the Dictionary might have had headings representing two or more people—for example, husbands and wives or other groupings—these have been broken down in the Explorer into individual entries, with one for each traveler. (There are some exceptions, such as where a lack of information made it impossible to identify individual travelers.) Cutting against the principle of individuation in the Explorer, however, is a thoroughgoing practice of interconnection, by virtue of various links (based on data points such as dates, places, and occupations shared by multiple travelers, to name a few) that encourage movement from one entry to another, in digital fashion. Yet at every stage, the transformation of the (print) Dictionary into the (online, digital) Grand Tour Explorer has required thinking through and deciding what may be lost as well as gained by moving a prosopography from page to screen. This is therefore also a story about biographical dictionaries in the digital era.31

Biographical dictionaries are not meant to be read from start to finish. In libraries they have traditionally sat among other dictionaries and encyclopedias in reference rooms, where information is organized and stored for easy consultation. Their structure is governed by the fact of their atomized content and arranged under headings, typically ordered alphabetically. In print, these dictionaries also lend themselves to cross-referencing. For example, some reference works put terms in bold to indicate a separate but related entry; in the case of the Dictionary, references to other entries are made by directing the reader to “see [x].”

In recent years, cross-referencing in online biographical dictionaries has gone well beyond the possibilities afforded by specific hypertext links, which constituted the initial added feature when text first moved online. For instance, born-digital Wikipedia has grown into the largest-ever encyclopedia in only twenty years, particularly on account of how it facilitates searching and sorting, allows and encourages reading as consultation, and enables readers to move across diverse kinds of content. Some have questioned whether it will even be possible for traditional reference works (such as a national biographical dictionary) to survive in this new context and have wondered what changes could help them to adapt to the online environment.32 The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) has been at the forefront of this conversation since its appearance online in 2004. It has survived in part through annual updates regularly adding new lives. The marvel of its searching capabilities, which awed reviewers on its very first appearance—“it is hard to think of any subject not illuminated by running word search through this colossal database,” wrote Keith Thomas at the time33—has only improved. Such are the wonders of metadata that readers now can search the ODNB’s lives by twenty different occupations, eight religious affiliations, and many of the locations and dates that appear within the biographies. Using a sidebar on the left, one can reach a desired entry, and within each entry, the names of people in blue represent hyperlinks to other entries. This ongoing discussion around and experimentation with online biographical dictionaries is the context within which we have transformed the print Dictionary into the digital Grand Tour Explorer.

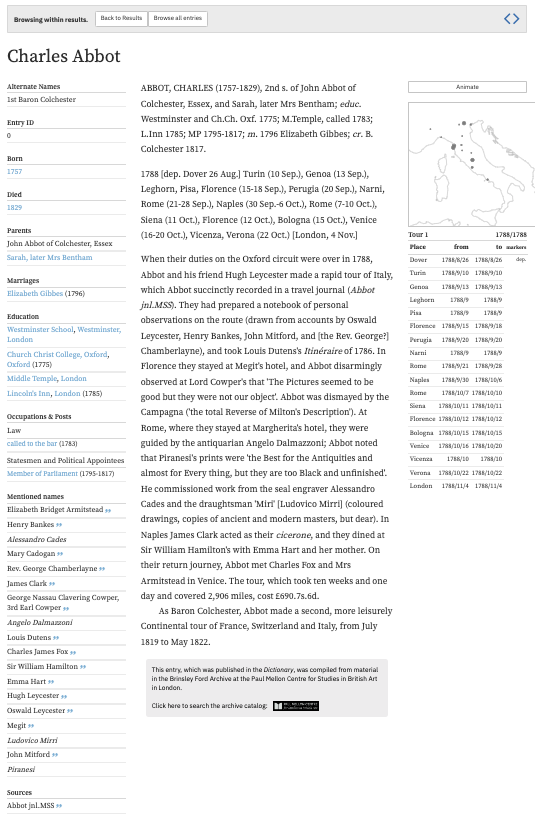

So what do the Explorer’s entries look like? Figure 4 shows an individual entry—in this case, that of Charles Abbot (1757–1829, travel year 1788), the alphabetized print Dictionary’s very first entry.

In the center is the text of the entry as it appears in the print version, preserving it down to the typography, and providing at the end a link to find the relevant material in the Brinsley Ford archive. This text, however, is flanked on either side by information derived from the print entry itself and formalized as data. The right-hand sidebar contains data about the travels (the sequence of recorded dates and places visited), as well as an animated map that visualizes this data. The left-hand sidebar contains the traveler’s biographical details, names of other travelers mentioned in the entry, and the entry’s sources—all sorted and grouped under the relevant category of data. Readers can scroll through all the entries in alphabetical order by moving with the arrow in the above banner right or left, similar to flipping through pages of the print Dictionary. They can also navigate from one entry to another, and they can explore several different entries by clicking on the links contained in the two flanking columns. Any name in hyperlinked font—a spouse, a parent, or any other associated traveler—is clickable and will take the reader to that traveler’s entry. Any of the other data points that appear clickable—for example, an occupation, a biographical date, a source on the left-hand side, or a place and time of travel on the right-hand side—will open up a list of all other entries that share that specific data point. Thus, a reader can easily navigate to (for example) a shared occupation (painter, member of Parliament, etc.) or to all other travelers born in a specific year or in a specific place at a specific time. On the Explore page, where all the categories of data appear as search fields, one can filter and browse in order to access all the corresponding entries. One can also explore multiple categories at once—for example, for travelers known to have traveled to Pisa and Rome between 1772 to 1775 who also happened to be members of the Royal Society.

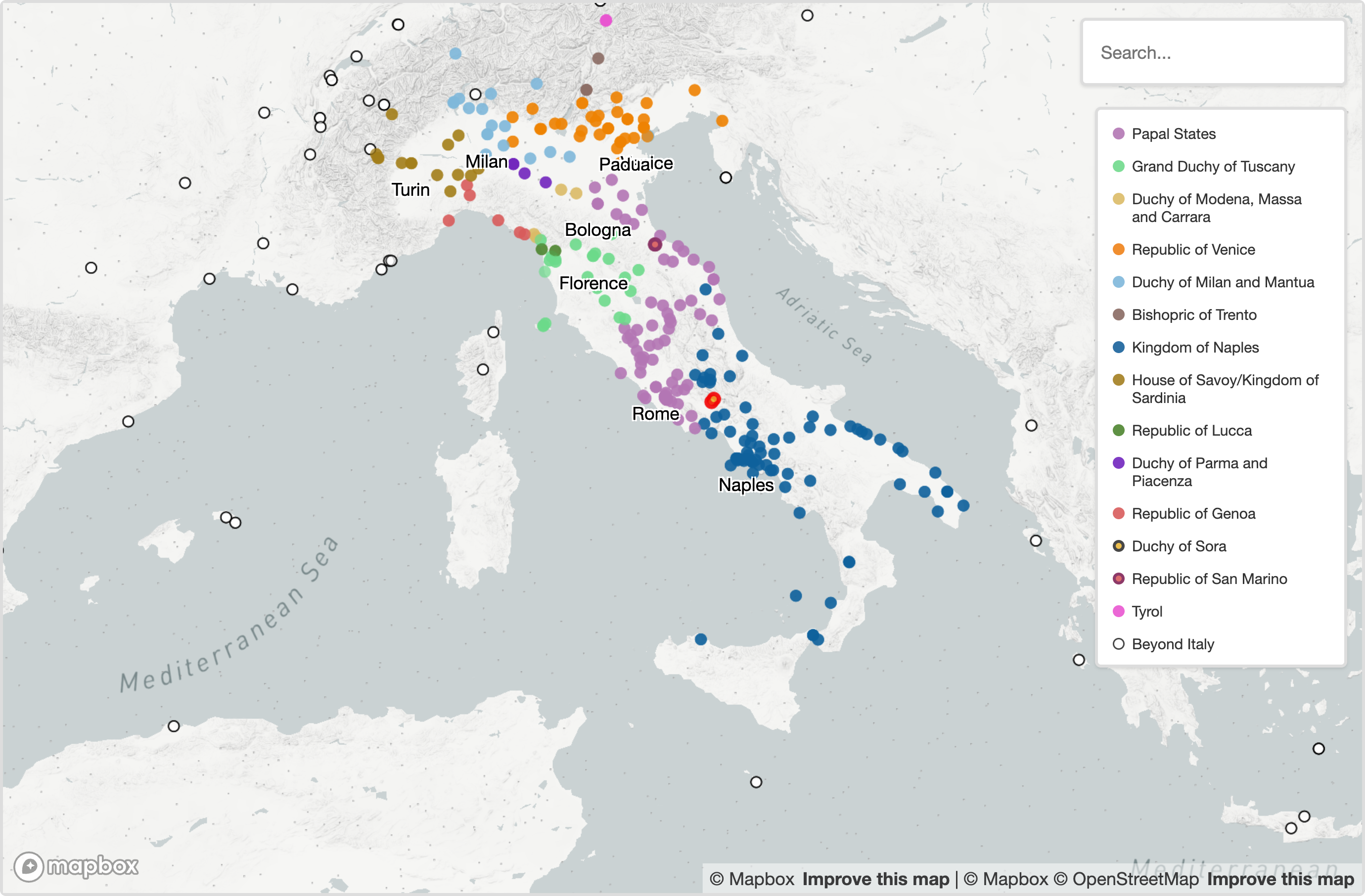

Given the significance of space to travel, the print Dictionary includes two maps to orient readers: a historical one from 1799, which shows roads and states at the time; and a modern one that includes more locations, but still falls short of including every place mentioned in the text or all the boundaries of the eighteenth-century states into which Italy was divided at the time. This is a difficulty shared by all works trying to convey the complexity of the political structure of eighteenth-century Italy, divided as it was into various states whose boundaries fluctuated. The Explorer map shown in figure 5 digitally resolves, in part, some of these issues. All locations in the database are present but become visible only when zooming in to avoid crowding and overlapping of labels. Rather than drawn boundaries on the map, the political entities are presented via different colors for locations, according to the states to which they belonged.

The map serves as a reference for readers: by typing in the search box any place mentioned in the Explorer, its location is shown. The map also operates as an additional interactive layer in the reading of this digital transformation of the print Dictionary: to click on any of the locations displayed among the database’s places of travel on the map is to be taken to a list of entries of the travelers who are recorded as having visited that location.

The list of entries is fundamental to the reader’s experience of the Grand Tour Explorer. Whether appearing as a vertical list showing the heading and first line of each entry, which readers can scroll as if they were reading an index, or as a horizontal scroll connecting one entry to the next, which readers can move along as if they were flipping the pages of a book, the list of entries is an essential touchstone. There is great power in this ability to explore and browse by multiple dimensions and readily access the results of these explorations in the form of lists of travelers’ entries. One downside to this digital transformation, however, is the loss of an immediate, physical sense of the whole print Dictionary. Readers know from experience what it means to hold a thick, weighty volume in one’s hands and to flip through its pages; they get a tangible sense of the abundant information and (in the case of a biographical dictionary) of the numerous lives that it contains. The physical experience of a book can also reveal, at a glance, the disparities in the information available for different individuals. One might notice that a certain individual’s entry is spread across several pages, while another’s is compactly contained in a single paragraph. This can even make certain imbalances, such as those of gender representation, immediately apparent: in a printed biographical dictionary, one might flip through pages and pages without encountering a single woman’s name among the entries.

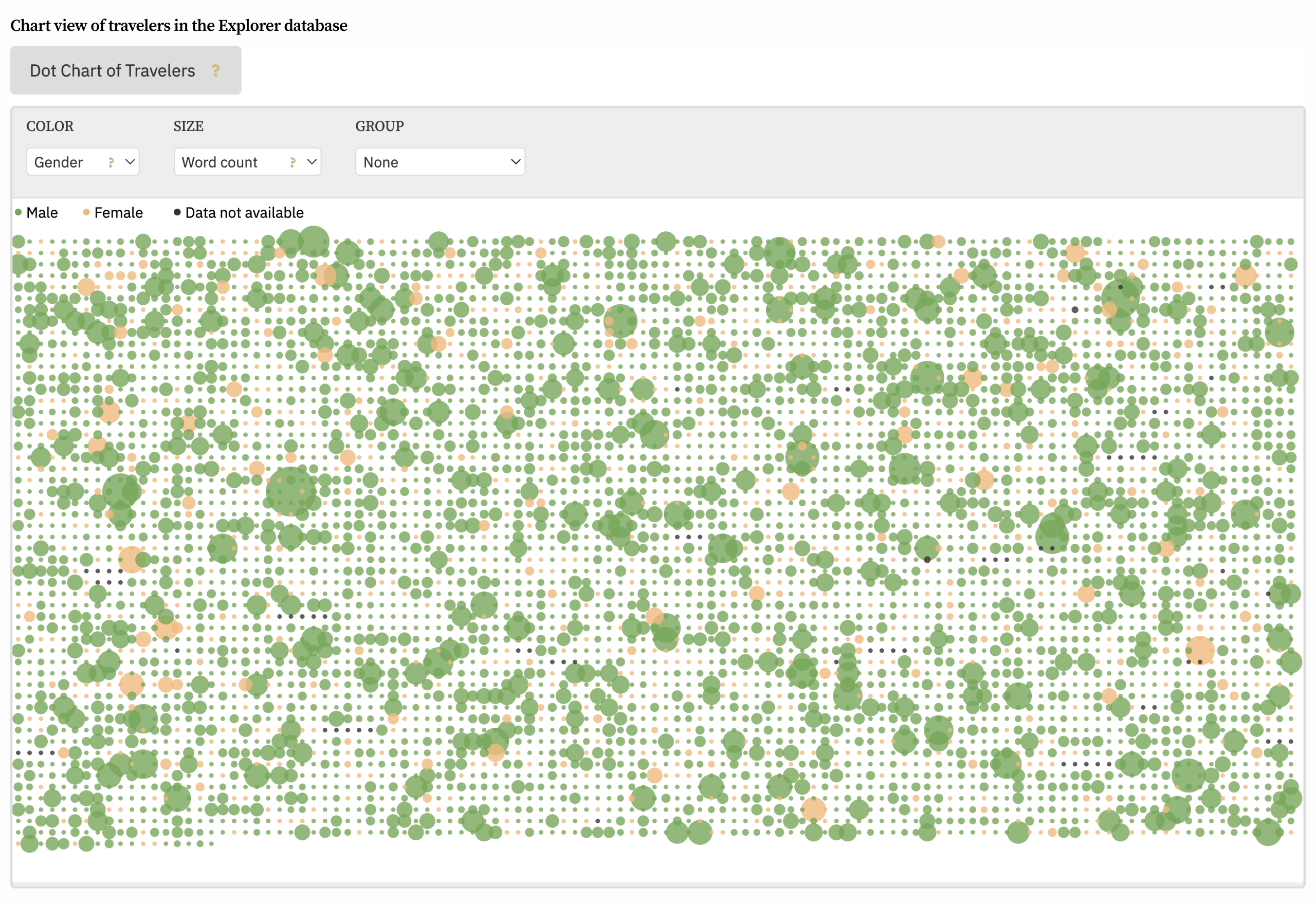

The dot visualization in the Grand Tour Explorer, shown in figures 6a and 6b, aims to convey a similar, if necessarily imperfect, sense of the database as a whole. This interactive visualization is designed to show all the travelers’ entries simultaneously and allow for sizing, sorting, and coloring to represent the variation in entry lengths, a process that is more immediately apparent in print, as well as the gender imbalance that one might grasp by flipping through the print Dictionary.

Hovering over an individual dot, readers can see the name of the corresponding traveler and, with a click, can visit the relevant entry. Readers thus can once again thread their way through different travelers’ stories, sorting and browsing in the distinctive manner that makes the Explorer a dynamic and augmented version of the print Dictionary, whose original texts are reproduced alongside the data retrieved from them. This creates a multidimensional reading experience in a more layered structure than, for example, in the online Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, with a functionality that extends well beyond basic search. The Explorer thus adds to the Dictionary not just by the inclusion of hundreds of additional travelers but also by ensuring that the travelers are perceived relationally and in aggregate. The individual travelers can easily be placed in evolving sets of wider horizons, by sorting and browsing various categories, which provides an expansive view of the world of eighteenth-century travel to Italy.

A Complex World of Data

The Explorer’s data, which can be easily downloaded for analytical purposes, allows readers to explore central questions about scale and representation in eighteenth-century travel to Italy and to investigate anew multiple facets of this world. The fully downloaded Explorer data consists of a staggering and complex number of data points about the journeys and lives of travelers in the database. There are close to half a million relating to the travels alone, in a mix of string, Boolean, and numeric data formalized to represent all the information about travelers’ journeys from the Dictionary. This amount is larger than any other open access data set available about eighteenth-century travel. And yet it falls short of what might have been: John Towner’s estimate that tens of thousands traveled puts the 6,007 travelers represented here proper context.34

Despite the massive quantity of information contained in the Explorer, readers who download it should be aware that the data is shot through with absences and uncertainties. What the Grand Tour Explorer presents is the Dictionary with all the richness and the limits of the information it assembled from multiple archives and sources. Many layers are represented in the data, each with its own version of missing information. There are the silences of the original archives—even the records in the “Note dei Forestieri” from the Venice state archives, supposedly recording all comings and goings from the Venetian republic, have their blind spots—not to mention the biases of other sources (letters and journals, for example) that reflect what individual travelers chose to record or simply leave out. The Dictionary does the astounding work of stitching together information from disparate archives to reconstruct these eighteenth-century travels, filling many gaps but also connecting overlapping uncertainties. Within it, one encounters unresolvable conflicts of evidence. For example, it places the future Cambridge professor of modern history John Symonds (1730–1807, travel years 1765–71) in Rome in March 1766, “about to return through Paris to London,” because this is what is stated by Laurence Sterne in a letter from Rome dated March 30, 1766.35 The next recorded location for Symonds in the Dictionary is May 1767, when he is said to be arriving in Florence from Bologna. But Symonds’s recently discovered manuscript journals show him in June 1766 touring Sicily together with the Neapolitan doctor and botany professor Domenico Cirillo, having arrived by land through the South of Italy. And in a letter to Linnaeus dated March 1, 1766, Cirillo announced his imminent departure for a trip to Apulia and then to Calabria and Sicily “with a friend.”36 Might Symonds have squeezed in a trip to Paris and London in April 1766 before making his way south with Cirillo? We simply do not know.

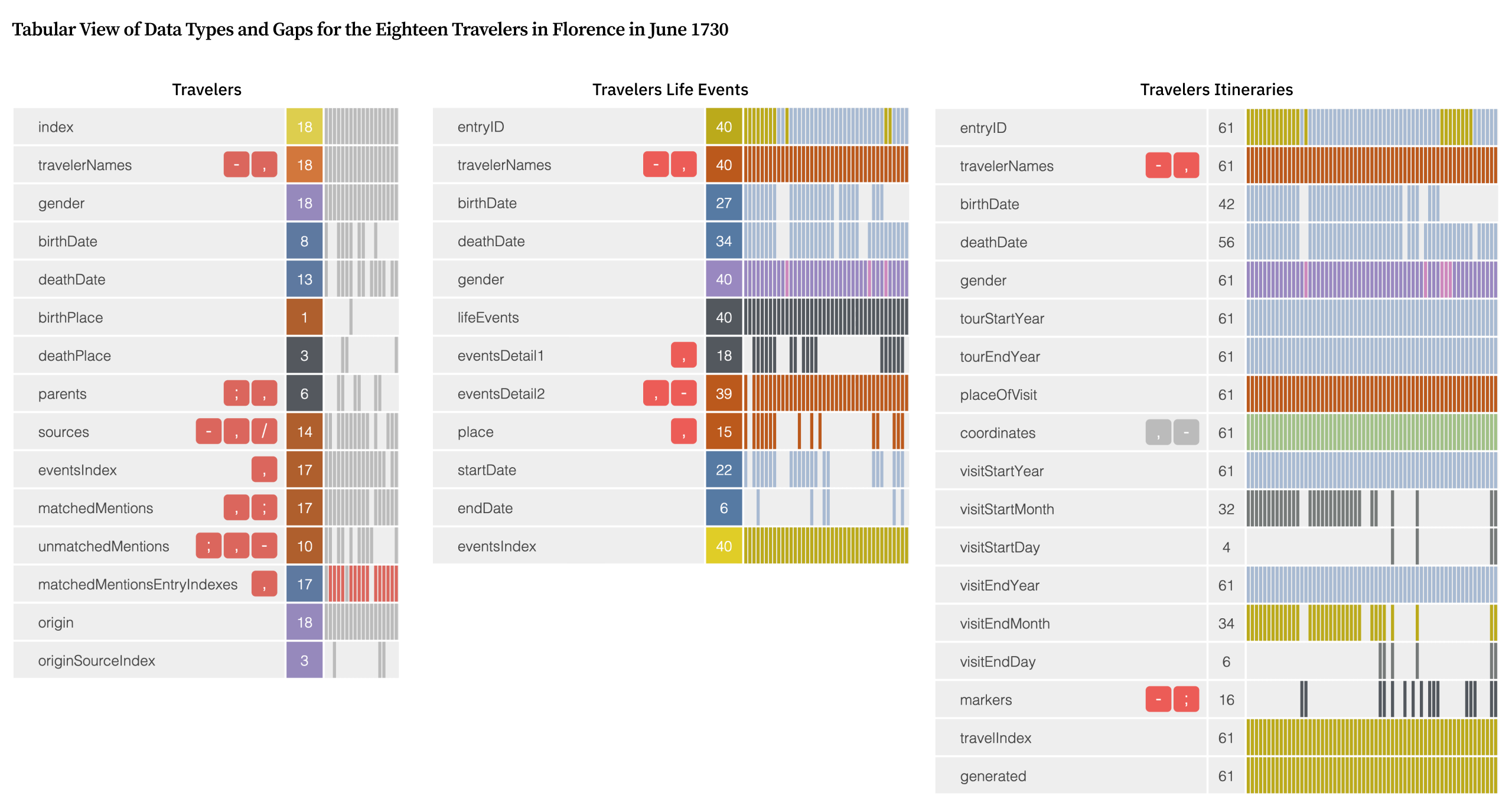

In addition to the irremediable gaps and inconsistencies the Dictionary (and subsequently the Explorer) inherited from its original sources, more were introduced through the selection process involved in assembling the Dictionary, and more complexity still was inserted by the choices made while transforming these printed records into Explorer data. The data itself, however, throws some of these patterns of presence and absence in the recording of historical experiences into sharp relief. This in turn helps readers grasp how the Dictionary represents information about eighteenth-century travel and gives rise to new understandings of the past.

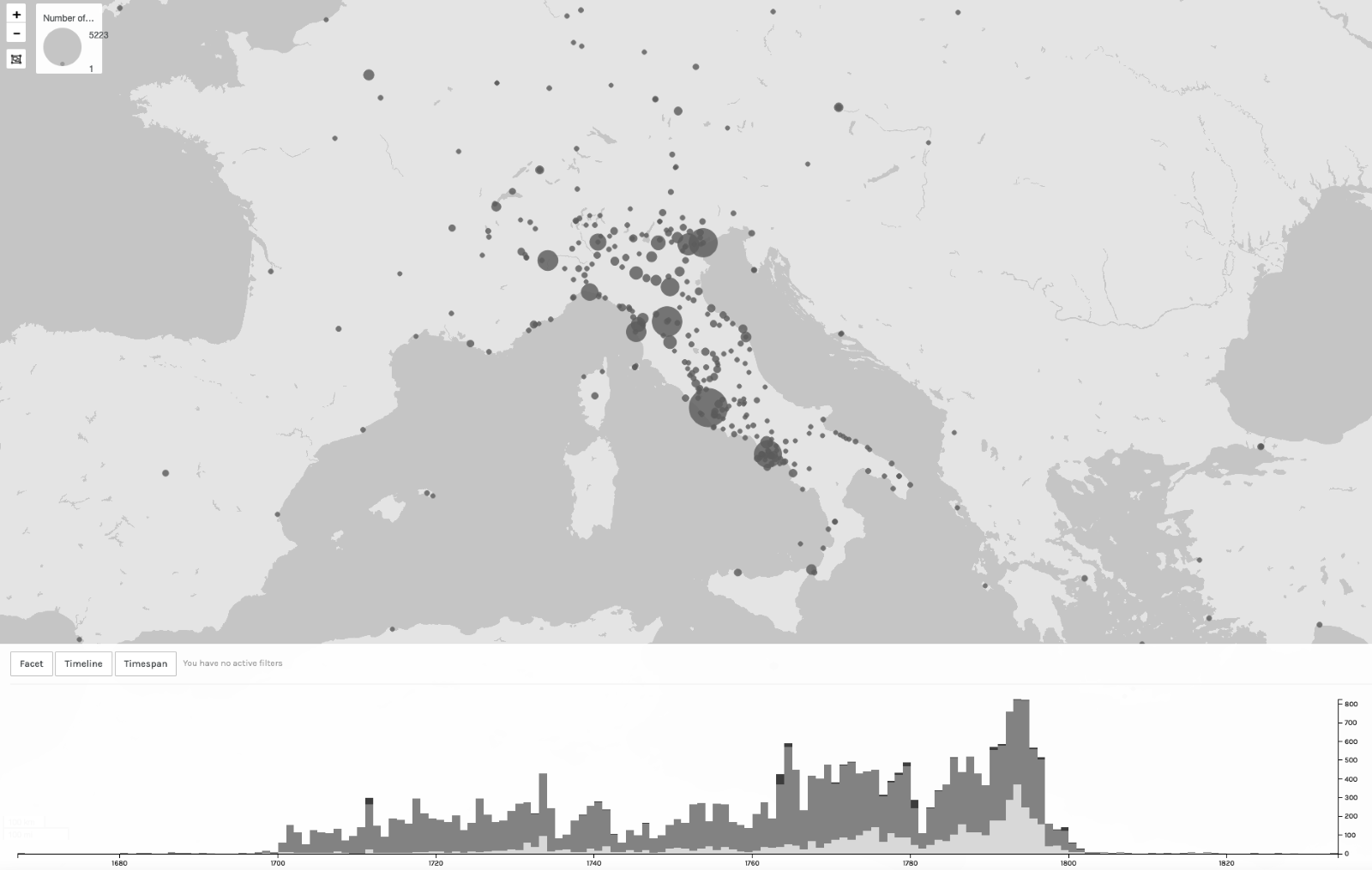

Any engagement with the data requires an understanding of its shape and meaning. The visualization in figure 7 enables consideration of all the travel data at once and represents all locations and years of travel recorded in the database for the Explorer’s 6,007 travelers.

The spatial data is mapped geographically in the upper band, where every dot represents a location, while the temporal data is shown as a timeline in the lower banner, in which each bar consists of all trips recorded for a given year. In the map view, the dots vary in size to indicate the number of visits to various locations. The largest dots mark the cities of Rome, Venice, Naples, and Florence, which is not surprising: the first three were the largest cities in Italy at the time, and all four were and are well-known tourist destinations. More unexpected are the places that appear as the next-most visited: Padua and Leghorn/Livorno. Padua was an important location, sitting along the way to Venice by land and housing (then as now) both famous art and one of the most ancient and prestigious universities on the European Continent (a destination in its own right). Yet the relative dominance of Padua—overshadowing larger, politically and culturally important cities such as Genoa, Turin, and Milan—owes as much to the source of the data: an archival register from the University in Padua, in which Anglo-Scottish (but also English, Welsh, Scots and Irish) students and visitors were eager to sign their names. Printed in 1921, this register constitutes the second-most-quoted source in the Dictionary and therefore in the Explorer; 641 records are drawn from it. It is also true that this register was well maintained only until 1730, and its use had petered out completely by 1765. Correspondingly, when one considers the presence of Padua in the travel data over time, this city drops significantly among visited places listed in the Explorer after 1730.

Conversely, there are places on the map that must have received many travelers but have been proportionally undercounted. Readers should be aware of the flight map effect of spatial data visualizations, which can distort perceptions of historical data. In the eighteenth century, travelers could not just skip over a place, nor could they necessarily speed through one. Out of the 3,383 travelers recorded in Rome, 698 appear to have been only there, but these travelers must have stopped and visited other places on their way to Rome. We can well imagine that places such as Bologna—on one of the main throughways from North to South and a destination in itself—must have had visits from more than the 671 travelers recorded in the database as having spent time there. Yet this information either went unrecorded in the sources consulted or did not reach the Dictionary, and it was subsequently not added to the Explorer database.

For many of the travelers, the entries gather precious information from disparate sources—ranging from official archives to travelers’ journals or letters to contemporary newsletters—and the result is a fragmentary travel record. For those traveling between Rome and Naples, for example, the passport check was at Capua; an official Neapolitan government document records with precision down to the day (with uncertainty, though, in the spelling of foreign names), when travelers stopped at this checkpoint, a document that was mined extensively to compile the Dictionary’s entries. For fifty-nine travelers in the database, this is all we have of their Italian journeys, but of course their tours extended beyond Capua.37 Even for better-known travelers with well-documented journeys, the travel data remains at times fragmentary. Anne Miller (1741–81, travel years 1770–71) documented her 1770–71 tour in regular correspondence that she published in 1776 as Letters from Italy, describing the manners, customs, antiquities, paintings, etc. of that country in the years MDCCLXX and MDCCLXXI, to a friend residing in France. Miller’s entry is indeed one of the longest in the Dictionary, being based on her published account and with additional references to other sources. The format of her published account—organized by letters, each with the date and location of when and where it was written—provides clear and well-structured data. But of the more than thirty places in Italy from which Anne Miller sent letters, only fifteen made it into the Dictionary and thereby into the Explorer. Only by reading the letters in full does one find all the other locations that she recounts having visited.

These observations do not diminish the value of the spatial information collected in the Dictionary and retrieved as data in the Explorer, but they do offer a caveat for how to consider and handle this data. The visualizations, as much as the data on which they are based, represent only what is preserved—surviving through many layers of records, each with its own mix of accidents and intentionality—as opposed to what might have been. Indeed, the map immediately tells readers much about the nature of the data itself and, with some careful examination, about the overall shape of the geography of travel in the eighteenth century.

Similar caveats apply when looking at the temporal dimension of the travel data, represented in full in the timeline in the lower band in figure 7, where each bar totals the number of travelers for that year. This is again made possible by the astounding work the Dictionary does of stitching together information from disparate archives to reconstruct these eighteenth-century travels, filling in many gaps but also connecting overlapping uncertainties. In this timeline visualization, some general patterns appear that are consistent with the consensus among scholars working on the Grand Tour. Over the course of the century, the number of travelers to Italy increases overall, but there are also lulls and spikes, often keyed to wars of this period. Decreases in travel occurred during the War of the Austrian Succession of 1740–48, the Seven Years’ War beginning in 1754, and the American War of Independence from 1775 to 1783. Increases occurred after the peace treaties of 1763 and 1783.

Digital humanities often confirm, by way of hard data, what is already known. This is often also a criticism of its limits. In this case it is quite striking that the overall picture of the Explorer data—formed from thousands of disparate bits and marked by absence and uncertainty—generally matches the ebbs and flows of history’s big events, such as wartime disruptions. This observation mostly tells us about the data and its integrity, but interrogating the data at a granular level—beyond the abstraction of the graph, by looking at the individuals who, in aggregate, constitute the bars in the graph visualization—offers even more insight.

The most pronounced dip in the number of travelers for the second half of the century is the bar for the year 1781, when only thirty-nine travelers in the database are recorded as having arrived in Italy, compared with 127 three years before and ninety-four just a year later. It is tempting to correlate this dip in travel with the fallout of the declaration of American Independence in 1776, when France allied with the United States and entered the war with Great Britain in 1778, joined by Spain the following year, and then the Dutch Republic. The Mediterranean became a war zone where armed merchant ships were granted rights to the cargo of any enemy ship taken as a prize (known as privateering). Indeed, this is the historical context for the story of the already mentioned British ship the Westmorland, which was one such “prize,” captured by a French ship in 1779, its cargo inventoried and put up for sale. The catalog of the Westmorland has survived, and its listing of the ship’s commercial goods along with art, books, and prints sent home by travelers both helped contemporary British travelers pursue their lost items and, more recently, has offered scholars a veritable time capsule revealing what Grand Tour collections were like. This Westmorland story is a concrete moment documenting the relationship between the Grand Tour and contemporary wars. To a degree, the 1781 dip in traveler numbers gleaned from our data does likewise.

What does a closer look at that year’s data offer? For twenty of the thirty-nine travelers reported to have arrived in Italy in 1781 we have some data and more context from the Dictionary. Two of these travelers arrived for their first tour: George Bruce-Brudenell Bruce (1762–83), traveling at the age of nineteen with a tutor by the name of Ferguson, and Thomas Clarke (b. c. 1742), an older Grand Tourist, traveling extensively after retiring from a military career. Others arrived who had already gone on tours of Italy. John Hanger Coleraine (1743–94) and George James Cholmondeley (1749–1827) did their Grand Tours when they were younger, but in 1781, they were following the magnetic Elizabeth Bridget Armistead (1750–1842) on her first trip to Italy. The sculptor Anne Damer (1748–1828) had first visited in 1779 but returned in 1781 for a second tour, this time accompanied by Lady Campbell (d. 1784). Also, the date on a small portrait of the collector David Digues Latouche (1729–1817), who had traveled before, places him in Rome at this time. A group of painters also arrived in 1781: Robert Fagan (1761–1816), Charles Grignion (1752–1804), Thomas Pye (fl. 1773–97), and James Smith (b. c. 1749–after 1797). Fagan and Grignion arrived together; Fagan had returned to London for one year but then came back to Italy for good, while Grignion came as a gold medal winner and also stayed on. Pye and Smith, who might have visited earlier, then lived out their lives in Italy. Other travelers came to visit relatives: Thomas Jenkins, the painter, dealer, and cicerone in Rome, is visited by his nephew James; John Udny, the merchant, collector, and British consul in Venice, is visited by a son; and Horace Mann, the British representative in Florence, is visited by his nephew Horatio (1744-1814), who brought along his young daughter Lucy.

The mere presence of all these travelers arriving in Italy in 1781 demonstrates that the war did not deter them, whether they were first-time visitors or returnees. Indeed, recent research shows that the French government decided not to discourage British travel during wartime, given the economic benefits to the French economy. Balancing the quantitative and the granular allows one to think through individual choices in the context of larger patterns. One might also discern specific consequences of the war on the Grand Tour. For Horace Mann, in particular, the data allows us to observe that he reduced his usual yearly visits to his uncle to every other year during the Anglo-French war. There is also a singular explicit mention of the war in relation to travelers arriving in 1781, concerning the Hon. Gen James Murray (1719–94), governor of Minorca beginning in 1774, who sailed into Leghorn/Livorno on August 31, 1781; the entry notes that “he evacuated his family during the French siege.” In fact, the text of the Dictionary tells us that Murray brought, along with his pregnant wife Anne Whitham (c. 1761–1824) and daughter, “about twenty other ladies.” Interrogating these absences and presences, and the individual trajectories that lie behind the bar charts, is a process that points beyond the simple use of data visualization for confirming known trends and instead toward new findings and questions.

More insight into the interplay of the quantitative and the qualitative and the meaning of numbers and of missing data comes from considering the counting done by many eighteenth-century travelers themselves. Travel was about observing and describing—using words and measurements for sites and monuments, as well as quotes and references and thick descriptions for customs and events. Tourists also watched and counted other travelers, reporting their numbers in the letters and journals describing their journeys. Joseph Atwell (c. 1696–1768, travel years 1729–30), the twenty-four year-old tutor to the twenty-year-old 2nd Earl of Cowper (1709–64, travel years 1729–30), reported in a June 1730 letter that there were “no less than 13” English in Florence. In letters to his mother during his first trip to Italy, dated February 1734, Richard Pococke (1704–65, years of travel 1733–34, 1737, 1740–41), the future bishop, pioneering mountaineer, and explorer of the East, noted about forty English in Rome. In February 1753, Lord North (1732–92, travel years 1752–53), traveling with his stepbrother of the same age (the 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, 1731–1801, travel years 1752–53) along with their tutor Christopher Golding (c. 1710–after 1758, travel years 1752–53), reported, “There are about 40 of our nation in Rome reckoning females.” Diplomats also reported on traveler numbers. The British representative in Florence for almost five decades, Horace Mann (1706–86, travel years 1732–33, 1738–86) gave regular updates in his letters to Horace Walpole (1717–97, travel years 1739–41) (after all, the numerous travelers were a major reason for his occupation). Mann noted twelve British travelers on July 21, 1744, thirty-five in August 1751 (“a larger flight of woodcocks than has been seen in many years”), and thirty-seven on October 18, 1768. In December 1772, he noted that over a few weeks’ time, the number of English travelers had dropped from nearly sixty to twenty. In May 1792, Lady Philippina Knight (1726–99, travel years 1778–99) wrote from Rome that during the spring, “we have had a hundred and fifty English here.”38

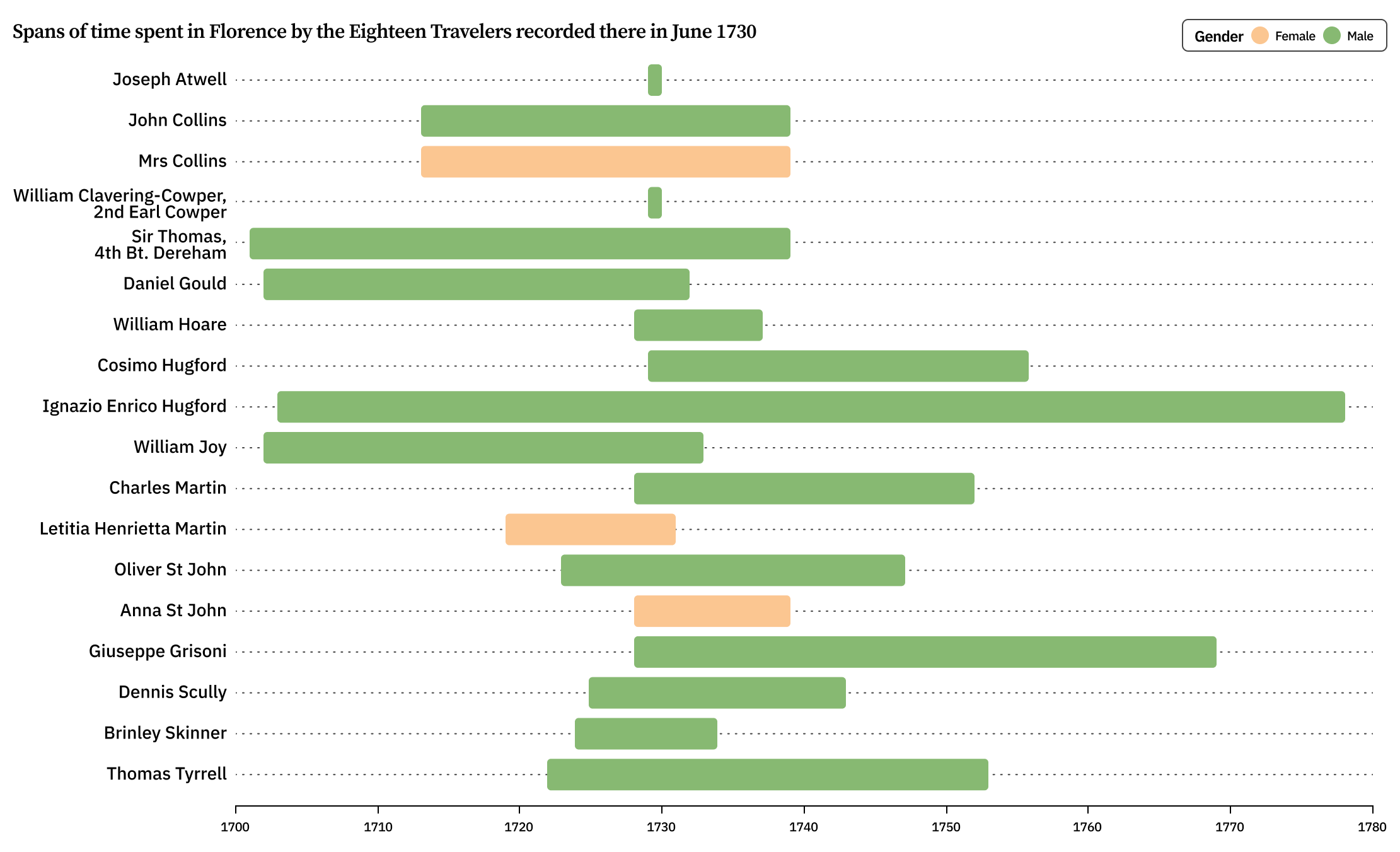

Even these few instances of travelers counting travelers show an increase in how many traveled over the century. One also wonders how these counts align with the numbers in the Explorer. For example, does a search in the Explorer database affirm Atwell’s “no less than 13 English” in Florence in June of 1730? Sixteen, which is the Explorer result of eighteen travelers minus Atwell and the young Earl of Cowper, is a close match. Yet, a closer look at these entries in the Explorer suggests that few if any of these travelers, besides Atwell and his charge, fit the profile of Grand Tourist; rather, many appear to be long-term residents, foreigners who found ways to make a living in Florence. In 1730 John Collins (fl. 1700–1739, travel years c. 1713–39) and Mrs. Collins (travel years c. 1713–39) had been in Florence at that point for about fifteen years, where they ran a hotel “for the Englishman that travels.” Sir Thomas, 4th Baron of Dereham (1679–1739, travel years 1701–39) was brought to Florence as a child and grew up there as a Catholic and Jacobite, attending to Medici interests. Daniel Gould (c. 1672–1732, travel years c. 1702–32) also lived in Italy, trying with mixed results for various consular appointments, as did Brinley Skinner (d. 1764, travel years 1724–34), whose father and grandfather had been British merchants in Italy. Dennis Scully (c. 1672–1732, travel years c. 1702–32) seems to have been another long-term resident, who appears in sources because of lawsuits and then his renting rooms to travelers. William Joy (1675–1734, travel years c. 1702–33))—originally a ship-carpenter from Kent—had been a performing strongman on the London stage who was then hired by the Grand Duke as his own strongman and came to reside in Florence for the next twenty years. Thomas Tyrell (d. 1753, travel years 1722–53), originally from Ireland, had been found by the Grand Duke as a child beggar in Prague and brought to Florence, where he became a courtier. The eighteen people counted by the Explorer in Florence in 1730 also includes artists and craftsmen. Charles Martin (travel years 1728–52), mentioned by many travelers and in diplomatic correspondence, was living in Florence as a painter and dealer. The two Hugford brothers—Cosimo (fl. 1729–56, travel years 1729–56) and Ignazio Enrico (1703–78, travel years 1703–78)—were also artists and dealers, whose their entire lives unfolded in Florence, where their father had moved from London to become a watchmaker for the Grand Duke. Laetitia Henrietta Martin (d. 1731, travel years 1719–31) had married the Florentine sculptor Alessandro Galileo in England and then moved back to Florence with him. Another British woman in Florence, Anna St. John (d. 1739, travel years 1728–39), had married the Italian painter Giuseppe Grisoni (d. 1769, travel years 1728–69) while he was working in London, and in 1728 they came back to Florence together. William Hoare (1707–92, travel years 1728–37), a student of Grisoni’s in London, came with them to spend ten years in Italy. Oliver St. Johns (c. 1691–1749, travel years c. 1723–47), Anna’s brother, seems to have moved to Florence even earlier; accounts of him as a disturbed “madman,” who was institutionalized, pepper the correspondence between Horace Mann and Walpole from 1723 to around 1747.

Whom among these sixteen did Atwell count? Reading through the entries, one wonders whether he might not have counted the Irish, the Catholic, the women, the artists, the long-term residents. Behind most clean numbers and clear quantitative measures, counting always requires a decision about categories and dimensions—for Atwell just as for the makers of the Dictionary and, indeed, for our own data assemblage.

Reading through the Dictionary’s entries raises the question of how these sixteen were identified and offers insights into different types of touring. Further reading would offer even more. As for the data alone, a visualization of a single data category or of a single traveler’s data would not enable us to meaningfully distinguish among them, per se, though more comes to the fore when looking at various data dimensions for the travelers in relation to each other and paying attention to what is missing as well as to what is there (see fig. 8). For example, among this group, some occupation data already indicates people who might not count as typical tourists, such as diplomats, an innkeeper, a strongman, and artists.

Close attention to the data, however, leads to rewarding insights. The Dictionary’s entry for Thomas Dereham is among the longest—in the top 5 percent—but while it underlines his role as an influential Jacobite presence and art collector in Italy, it does not mention his lifelong correspondence with the Royal Society on a number of scientific topics. By paying attention to the Explorer’s societies data for Dereham, though, which records his Royal Society fellowship, one is directed to his scientific interests. There are also ways to examine and visualize the data that get one closer to interpretative questions. If, for example, one visualizes the data to show duration of tours, “Atwell” and “Earl of Cowper” emerge quickly as the outliers (see fig. 9). While they are attested in other types of data, they are also the ones who spent the least time in Florence. This shorter time spent sets these two Grand Tourists apart from the long-term resident; everyone else stays much longer, including visiting artists. But, then again, the question arises of “whose Grand Tour?” How do we account for these British travelers who end up staying much longer in Florence? How much a part of the Grand Tour world are they? After all, the innkeeper Collins’s daughter, Anna Maria Collins, born in Florence, ended up marrying a visiting Grand Tourist and moving back with him to London to participate fully in a post–Grand Tour life.

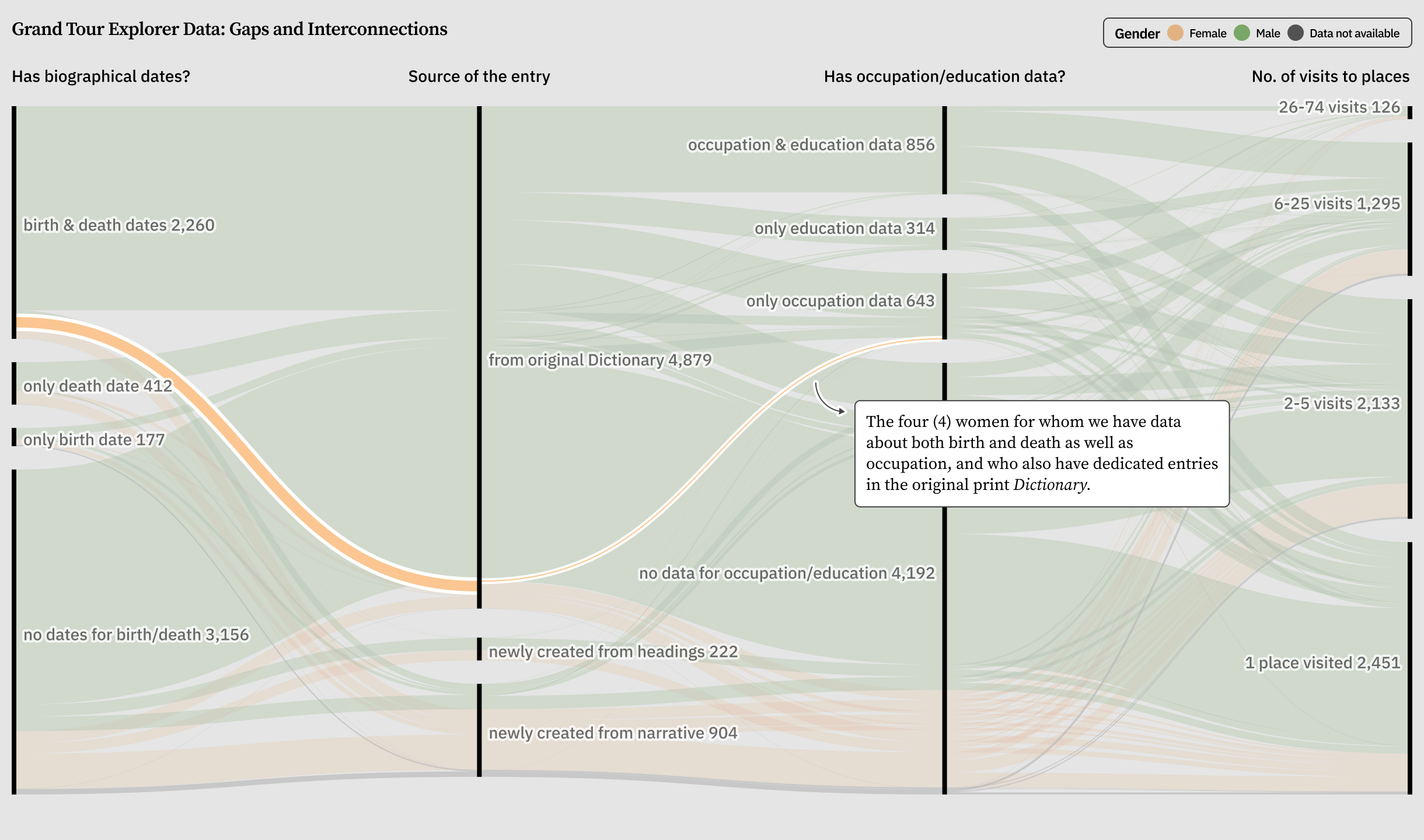

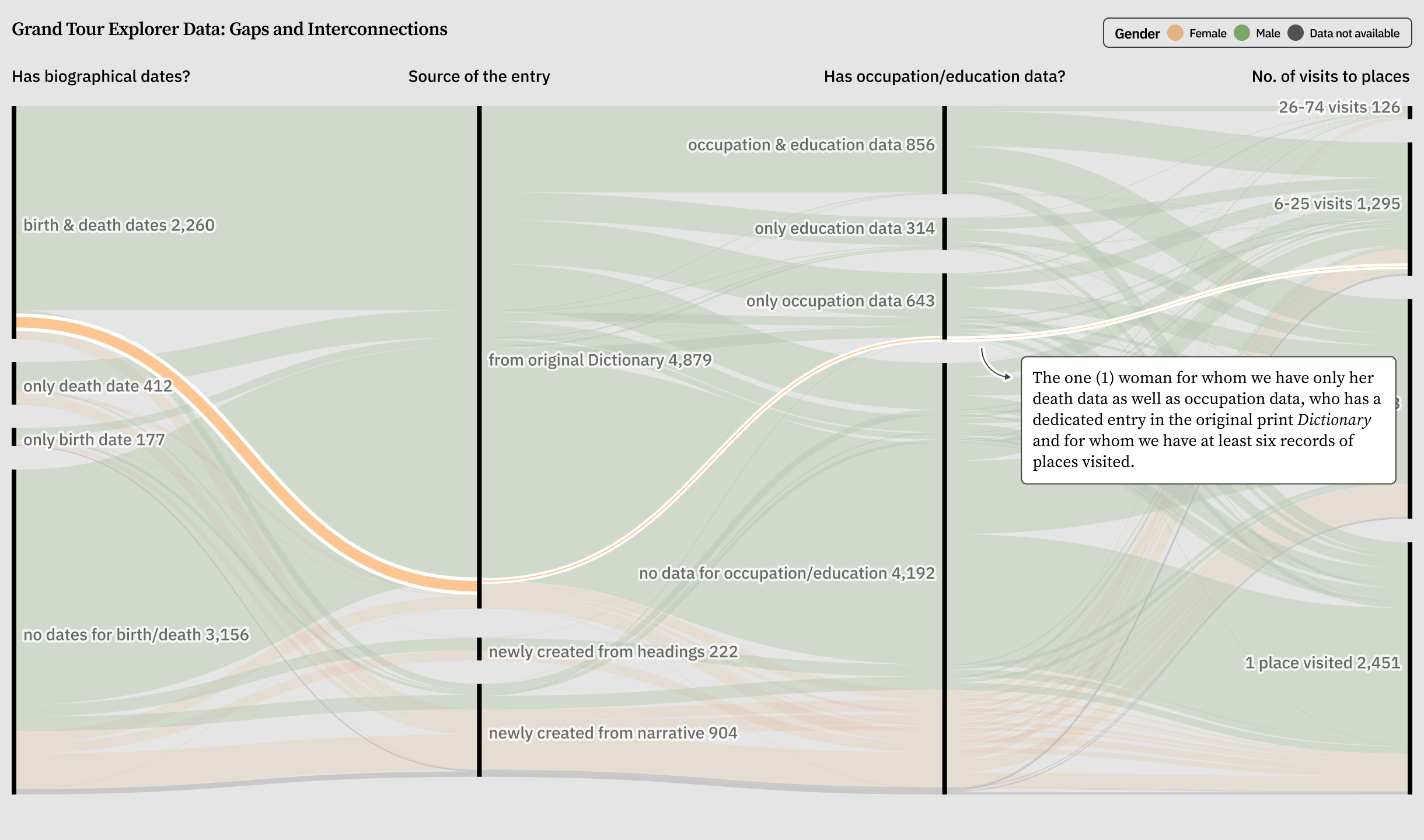

Historical data—that “saber-toothed tiger”—is most revealing when approached with a systematic interest in understanding its gaps as well as its interconnectedness. When downloading the Explorer data and separating it from its original context, it is most important to keep in mind its sources and the meaning and character of its original categorization. Only then can one use the data to make new connections and interpretations. The visualization below illustrates this point further (fig. 10). This graph of parallel sets visualizes the whole data set of travelers at a glance in terms of four dimensions: (1) biographical dates—birth, death, either, or neither; (2) origin of the entry—whether the traveler had an entry in the original print Dictionary or had one newly created for the Explorer; (3) occupation and education—that is, data concerning one or the other, both or none of these dimensions; (4) how many visits to places are recorded in the travelers’ data.39 This visualization presents only one set of categories and in one particular order, but the principle of interconnectedness and the reality of gaps in the data are the key takeaways.

For example, immediately apparent is which travelers are by and large best documented: men. These are most likely typical elite Grand Tourists, for most of whom we know dates of birth and death, as well as much about their lives (for example, occupation and education), and who have better recorded tours with multiple places visited. But what is also immediately apparent, and perhaps more surprising, is how many of these travelers (as many as two-fifths of the set) are shown in the recorded data to have visited only one place. This surely reflects gaps in the data; however, it is essential to appreciate that, for many, we have additional information in other categories and thus to realize that these travelers have something to tell us about the world of the Grand Tour. Engaging interactively with this visualization reveals, for example, that there are four women for whom the data records both biographical dates and occupation data, but one woman for whom we have only the date of death and occupation data (figs. 11a and 11b). Nevertheless, this woman traveler ranks among the better documented, with between six and twenty-five place visits recorded.

Another important category is that of source of entry (labeled in the data as entry origin). The parallel sets visualization shows that a clear majority of the entries—4,879 out of 6,007—are from the original Dictionary. But 222 are “newly created from headings;” in these cases, entries that pertained to multiple travelers in the Dictionary were turned into individual entries for each traveler, changing the heading to reflect an individual traveler’s name, maintaining the same entry text as in the original Dictionary, and curating the additional data for each by hand. The “newly created from narrative” category—which includes 906 entries—pertains to travelers who were in the Dictionary but subsumed in others’ entries, most often women who appeared under the headings of their husbands. There is more to say about these newly created entries, and the recovery of these hidden figures of the Dictionary is recounted in “Archive to Explorer”—but for now, note how these travelers who appeared only in the background in the Dictionary have become part of the knowable world of the data. Although much less is known about many of these hidden figures—the great majority of them women—this data and the intersecting lines that animate it point us to new questions and tell us new stories.

Doing Research with the Explorer: Seven Scholars’ Essays

A World Made by Travel shares Grand Tour data publicly, thus opening new research possibilities to all. At the same time, it features several original studies conducted using the Explorer and its database. This scholarship was produced by researchers who specialize in areas related to the Grand Tour (“domain experts,” to use data science parlance) while the Explorer was being created. A number of scholars of eighteenth-century British travel to Italy accepted invitations to participate in two workshops held in 2016 and 2017. At these convenings, participants generously worked through research questions of their own while using the Explorer. Some were already familiar with digital humanities work; for others this was their first experimentation with digital history and with the idea of working with data. All brought an intensive knowledge of archives and of the historical world of the Grand Tour. The conversations during these workshops informed the final shape of the Explorer and provided an opportunity to showcase how data work and data visualization can support original scholarship.

The essays included here demonstrate powerfully the varieties of new research made possible by the Grand Tour Explorer. Open access to the Explorer—both to the abilities to browse, search, and sort and to the underlying database itself—will in time produce more and unexpected scholarly work, yet some features of what such research may look like are already apparent. The intensity of engagement with the data fluctuates; some scholars rely on word searching, for example, and some research questions are addressed through only a subset of the 6,007 travelers. All studies show the importance of contextualizing the work done with the Explorer’s data through further research and careful engagement with primary sources and the secondary literature. The newly populated world of travelers made accessible by the Explorer, which renders equally observable and searchable both elite and nonelite travelers, and which includes underdocumented as well as previously hidden figures, has encouraged research about travelers who were less visible before this digital transformation. The scholars’ essays in A World Made by Travel—alongside the study of sixty-nine architects in the Explorer that my team and I published in 2017 in the American Historical Review40—are the first to use the Explorer. Taken together, these essays show scholars using the Explorer effectively to look for unexplored facets of the world of the Grand Tour—seeking the Italians, for example, or focusing on specific types of (nonelite) travel or traveler or on specific activities and interactions. In some cases, scholars have done so by looking at large numbers, in others by focusing on smaller sets, but all exemplify deep historical work achieved by engaging with the Explorer’s data, in combination with attention to context and sources beyond its bounds, to collectively rejuvenate the study of eighteenth-century travel to Italy.

Rosemary Sweet’s “Who Traveled, Where and When? Using the Grand Tour Explorer to Examine Patterns of Travels and Travelers,” extends Sweet’s distinct interest in urban centers and tourists’ experiences to consider cities beyond the top five that her previous work illuminated, using Explorer data on travel to Turin, Milan, Genoa, Leghorn/Livorno, and Bologna.41 Building on the travel data for these cities, Sweet probes patterns of representation in the Explorer’s data, integrating these findings with her knowledge of eighteenth-century travel accounts, both published and in manuscript. She detects that by the last decades of the century, women had come to surpass young men in the numbers of recorded travelers.

Rachel Midura, in “The British Arrival in Italy,” builds on her expertise in postal routes, transnational history, and data science to posit tourists’ possible access routes into Italy, paying attention to geography and travel technologies. Despite data limitations, Midura models sophisticated data analysis tying relations between infrastructure growth and travel patterns to historical developments. She also points to further questions about travel and gender, and family and groups versus individuals.42

Melissa Calaresu’s research has long focused on recovering and understanding the Italian (and particularly the Neapolitan) presence in the European Enlightenment.43 In “Life and Death in Naples: Thomas Jones and Urban Experience in the Grand Tour (Explorer),” Calaresu focuses on the painter Thomas Jones’s relationship with Italy’s people and with their urban and domestic lives, finding in the Explorer traces of engagement beyond the touristic mode and seeking the occluded presence of Italians. Calaresu uses the length of time spent traveling as a significant measure of travelers’ engagement with a place and thus rewrites travel patterns and their assumed meaning.

In her essay “Ciceroni and Their Clients,” Carole Paul, a scholar interested in the relationship between people and the art they experience in museums or public spaces, examines another understudied figure in the world of the Grand Tour, that of the ciceroni who guided tourists around sites and educated them about these places’ history and art.44 With the help of the Explorer’s various tools, Paul finds fifteen ciceroni, twelve of whom have their own entries in the Explorer, and she identifies 142 of their clients among the Explorer’s travelers. While acknowledging that there were many more clients, and also more ciceroni, Paul’s systematic examination of the data for the group she has identified nonetheless leads to a fuller sense of the careers of the ciceroni and of the types of clients who employed them.

Sophus Reinert, an economic historian who considers travel in the context of emergent capitalism and international competition, went looking in the Explorer for “the economic Grand Tour.”45 “Mapping the Economic Grand Tour: Travel and Emulation in Enlightenment Europe” is the result of his search for travelers whose journeys attest to economic interests, ranging from merchants to early economic thinkers. Reinert finds evidence of distinct patterns in the data for these Grand Tourists, while making the case for why these types of travelers help us to understand more fully eighteenth-century travel to Italy.

Catherine Sama, in “Going Digital: Re-searching Connections between Rosalba Carriera and British Grand Tourists,” also explores the Italian-British divide, drawing on her expertise on women in early modern Venice.46 Sama focuses on Rosalba Carriera, who as an Italian artist did not receive an entry in the Dictionary. Using mentioned names and their networks, Sama reconstructs a full set of relations to better understand Carriera’s life and work, including discovering new sources describing her studio in Venice.

Finally, in “Harlequin Horsemanship: Non–Grand Tourists on the Grand Tour (Explorer),” Simon Macdonald, an expert on transnational history, and particularly on British people living abroad in early modern Europe, builds on his discovery in the archives of one British equestrian showman in Italy by using the Explorer to look for more.47 The resulting data set enables MacDonald to construct an unprecented historical narrative of British equestrian shows in Italy, while also reflecting on the archival possibilities and limitations built into the Explorer itself.

Cumulatively, these essays propel the study of the Grand Tour forward. They also demonstrate some of the most significant benefits of the transformation of the Dictionary into the Explorer (along with foregrounding the Dictionary’s hidden figures) to be not so much the total mass of data it makes available as much as the Explorer data’s density of information, the systematic nature of the categories that organize its information, and the clarity about its boundaries and limits as an information data set. In the Explorer, researchers can see, as if for the first time, what has remained stubbornly uncertain about the Grand Tour. Crisscrossing between data sets facilitates original questions and innovative interpretations, even as knowledge of the sources, archives, and context—that sticky historiographical concept—remain the key to approaching this information.

A World Made by Travel and Digital History

Together with colleagues in the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project at Stanford University (the umbrella project from which the origins of A World Made by Travel emerged), I first wrote about the possibilities and challenges of doing historical research in the digital age in 2017. We reflected on working with historical sources as data in a time of rapid digitization and “datafication” and about working with printed and some archival material that was becoming available online as jpegs, pdfs, html texts, and metadata shared by repositories. Also under discussion was the multifaceted richness of early modern historical data, traversing time and space and connecting people, and how this richness coexisted with the inherently incomplete nature of this type of data. We stood by our dedication to the interplay between the quantitative and qualitative as essential, and we hoped to refine the concept of “big data” such that it would take into account interconnectedness rather than merely size and number. We discussed our filtering, plotting, measuring, parsing, and visualizing of information as data and our own experience of stepping back and observing this data’s contours—how this prompted us to take a closer look at underlying patterns and forgotten figures while remaining aware of that data’s fragmentary character. In the air was a possible future in which scholars could seamlessly share and analyze one another’s findings, using linked data to identify overlaps with existing data sets and to interact with new ones.48

Now, just a few years later and on the other side of the social and technological ruptures entailed by a global pandemic and the spectacular rise of AI, the concept of data is at the forefront of essential conversations more than ever, both in the academy and beyond. Three major journals in their respective humanities fields (History and Theory, Critical Inquiry, and New Literary History) published special issues about data in 2022 and 2023, just as the publication of A World Made by Travel was under way.49 From megabyte to zettabyte, the exponential growth of data represents a new structural condition, and the constructed nature of data is at the core of reflections about history in the digital age. Drawing a contrast with earlier forms of cliometrics, Claire Lemercier and Claire Zalc, for example, call themselves “alternative quantifiers” and emphasize the messiness of data, pointing to the interrogation of assemblages’ layers not only for what is missing but also for how they overlap, and how outliers can reveal specific forms of interaction among categories.50 The ongoing growth of data as both an object of discourse and an epistemology in its own right, a way to think, poses these questions more urgently than in 2017. Indeed, it is increasingly crucial to highlight counting as a historiographical act—not merely a passive means of registering information but a way (for better or for worse) to actively establish categories and produce knowledge.